Table of Contents

- Preface

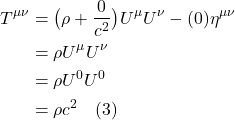

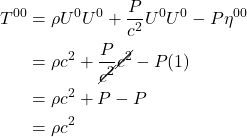

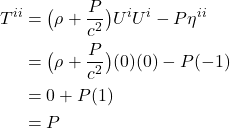

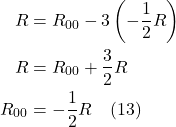

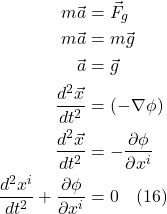

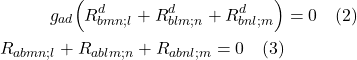

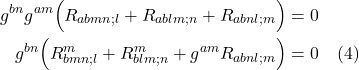

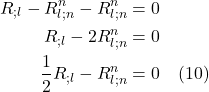

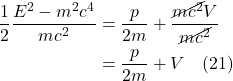

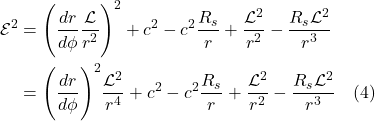

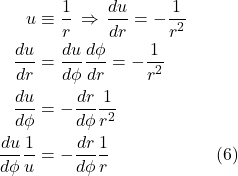

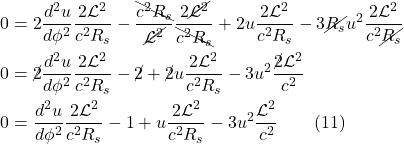

- I Introduction

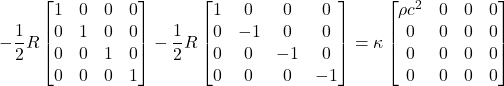

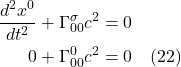

- II Curvature

- III Einstein Field Equation

- IV Schwarzschild Metric

- V Confirmatory Evidence

Preface

These are some notes on general relativity. As in most of my pages, this is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather, to cover the basics and select topics that I feel I can better remember if I write them down.

As usual, explanatory notes can be accessed by clicking the appropriate link, often labeled “here.” To close the explanatory note, click the link again.

I. Introduction

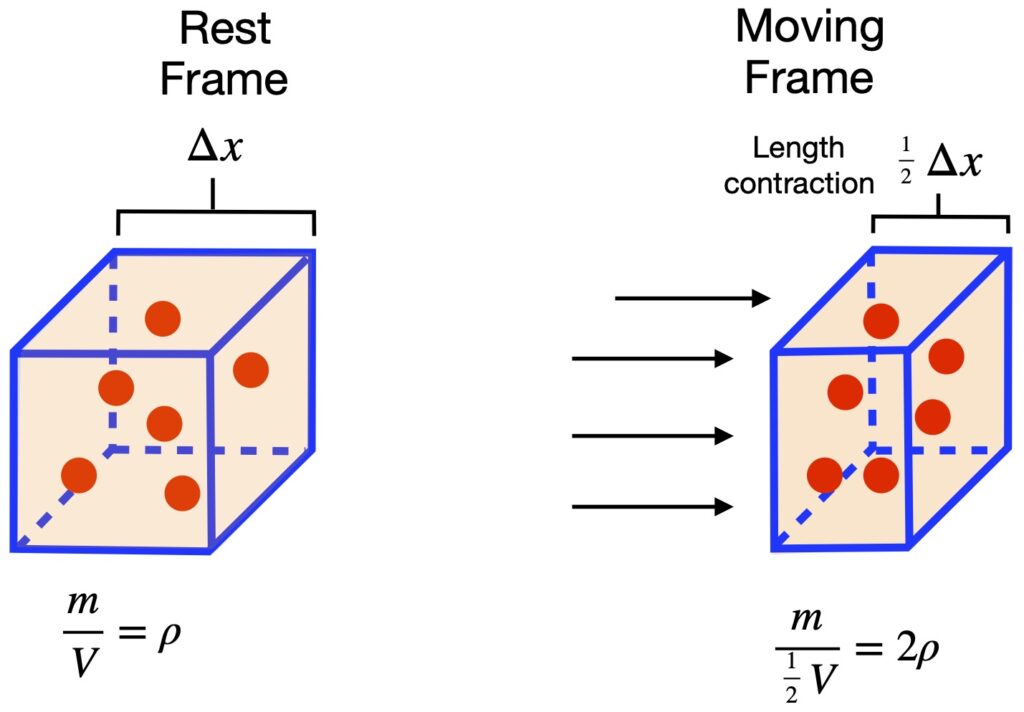

Albert Einstein published his well-known paper on special relativity in 1905, a paper that described how lengths and time intervals vary depending on one’s frame of reference. However, this theory applies only to inertial frames of reference (i.e., frames of reference involving bodies that are at rest or moving at constant velocity). He wished to extend this theory to non-inertial (i.e., accelerating) frames.

I.A Equivalence Principle

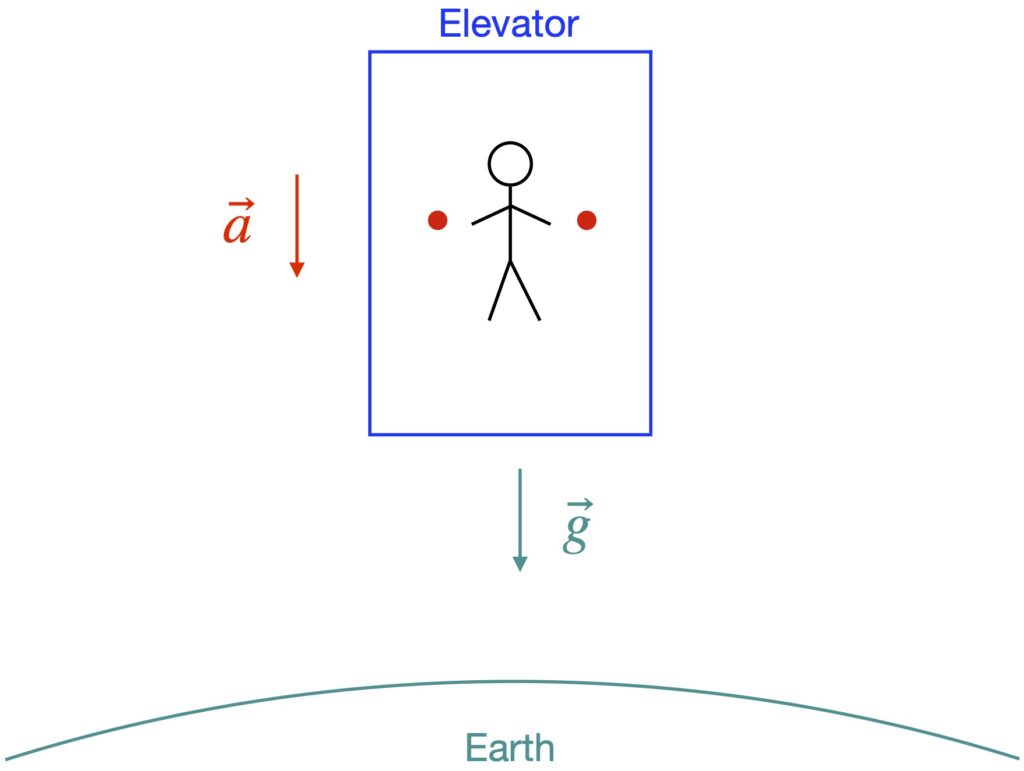

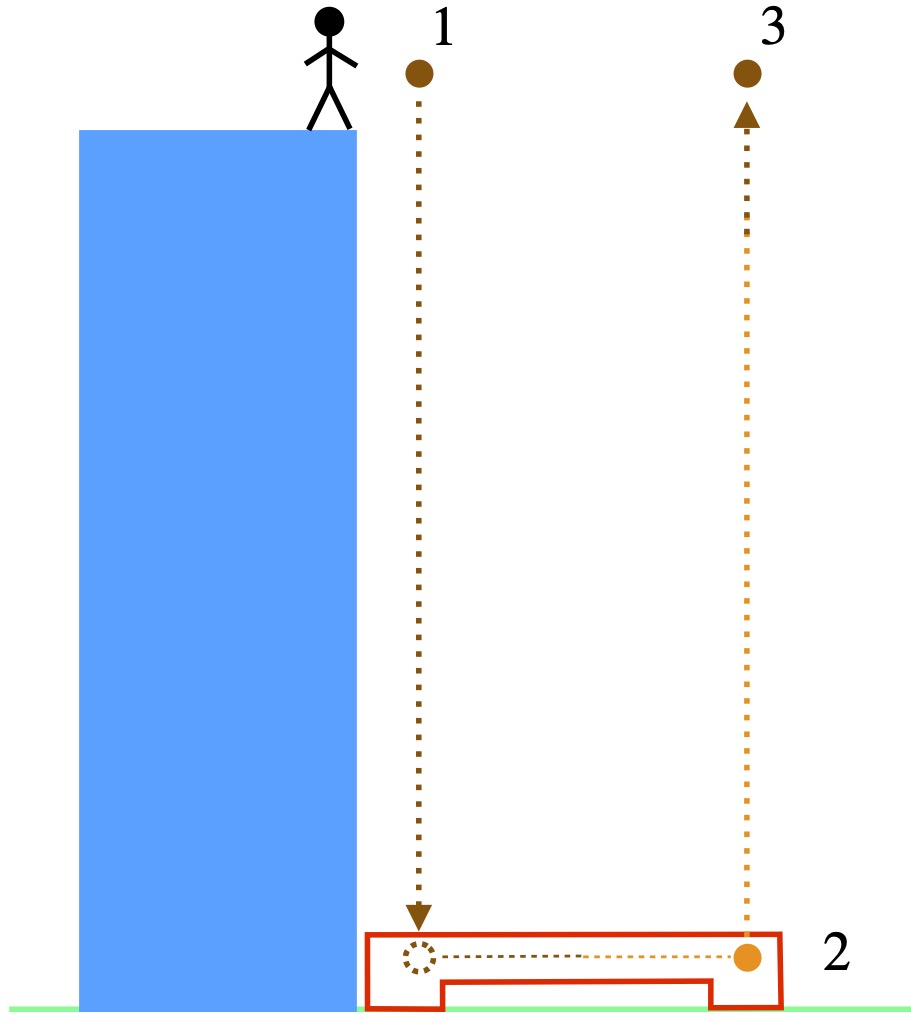

His path to accomplishing this began in 1907 when, while sitting in his office in Bern, Switzerland, he had what he called “the happiest thought of [his] life.” He realized that a person in free fall from a rooftop does not feel his/her own weight and that objects that are falling with the person will continue to fall along side the person until they all hit the ground. The concepts embodied in this thought experiment are referred to as the equivalence principle and have been presented in several alternative forms over the years, most notably as an observer in an elevator that’s been dropped off a cliff, plummeting toward earth under the influence of gravity with an object (such as a ball) falling beside the observer. Such an arrangement is depicted in figure I.A.1.

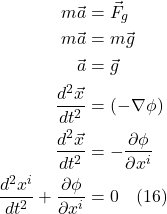

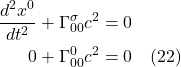

In the diagram, we see an elevator in free fall with an observer and 2 red balls “floating” within it. We know from Newtonian physics that:

![]()

where

![]() is the force on an object

is the force on an object

![]() is the object’s mass, sometimes referred to as the inertial mass

is the object’s mass, sometimes referred to as the inertial mass

![]() is the object’s acceleration

is the object’s acceleration

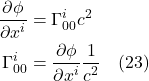

The force, in this case, is the force of gravity which, in Newtonian physics, is given by:

![]()

where

![]() is the gravitational force between 2 objects

is the gravitational force between 2 objects

![]() is Newton’s gravitational constant =

is Newton’s gravitational constant = ![]()

![]() and

and ![]() are the masses of the object, sometimes referred to as the gravitational mass

are the masses of the object, sometimes referred to as the gravitational mass

Here, I use ![]() and

and ![]() for the masses in the Newton’s equation of gravitation because, in our example, I’ll let

for the masses in the Newton’s equation of gravitation because, in our example, I’ll let ![]() represent the mass of the earth and

represent the mass of the earth and ![]() the mass of the smaller objects (i.e., the elevator, the observer, the balls).

the mass of the smaller objects (i.e., the elevator, the observer, the balls).

Now we substitute eq. (I.A.2) into eq. (I.A.1). We get:

![]()

We can cancel ![]() on both sides. This gives us:

on both sides. This gives us:

![]()

Now let’s examine the units of the right side of eq. (I.A.4):

![]()

Here,

![]() is mass

is mass

![]() is length

is length

![]() is time

is time

We’re left with a term that has the units of acceleration, a term I’ve called ![]() , the acceleration due to gravity. Thus,

, the acceleration due to gravity. Thus, ![]() , the acceleration of the object affected by gravity equals the acceleration created by the gravitational force,

, the acceleration of the object affected by gravity equals the acceleration created by the gravitational force, ![]() . Note that these accelerations do not depend on the mass of the falling object, a well-known experimental result that legend has it Galileo established by dropping things from the leaning tower of Pisa. A basic principle we can extract from this little exercise is that inertial mass is equivalent to gravitational mass.

. Note that these accelerations do not depend on the mass of the falling object, a well-known experimental result that legend has it Galileo established by dropping things from the leaning tower of Pisa. A basic principle we can extract from this little exercise is that inertial mass is equivalent to gravitational mass.

This seemingly simple idea has some profound consequences. First off, it explains why our observer in the elevator and objects next to them float weightlessly in the elevator as they fall: namely, because the frame of reference of the elevator is accelerating, and any observer in their own frame, don’t think they’re moving. Thus, over a sufficiently small region of spacetime, the frame of reference of an object in free fall is equivalent to an inertial frame of reference.

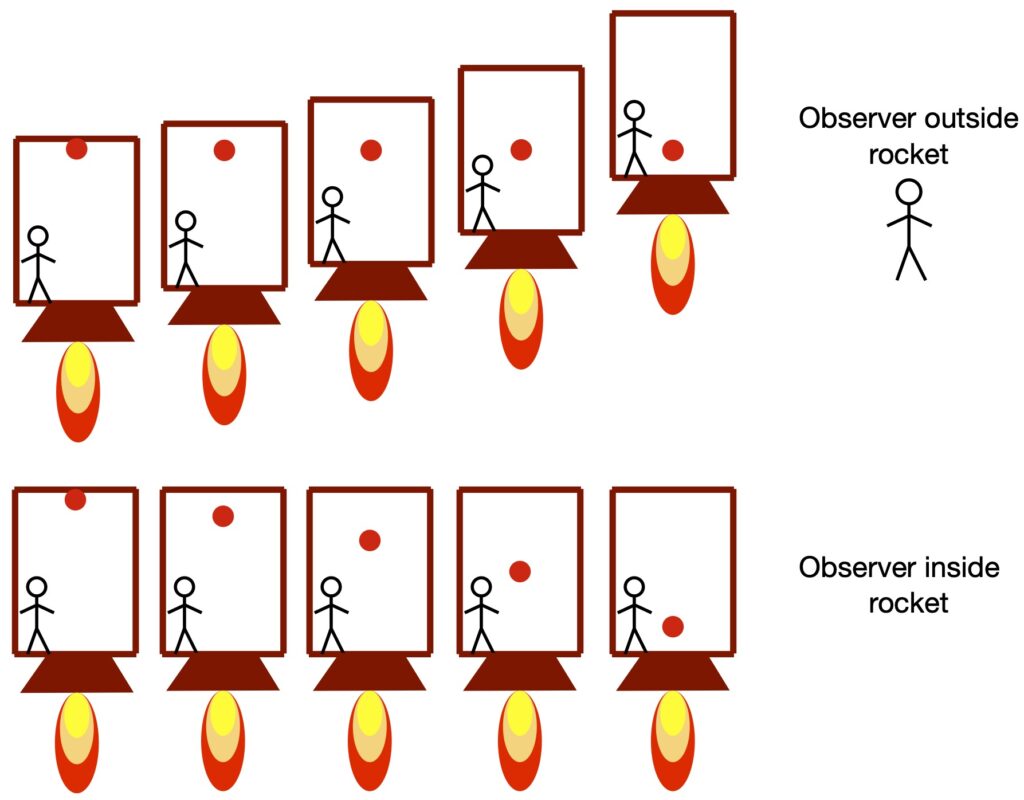

To see additional consequences of the equivalence of inertial and gravitational mass, let’s expand our thought experiment and imagine an observer in a rocket with a (red) ball at the rocket’s ceiling (figure I.A.2). Of course, if the rocket is moving at constant velocity (to an observer outside the rocket) or if the rocket is in free fall, the observer and the ball do not move. But now imagine that the rocket accelerates upward (relative to the observer in the rocket, to the ball in the rocket and to an observer outside the rocket) at 9.8 cm/sec, the acceleration known to occur due to the earth’s gravity . The observer outside the rocket sees 1) the rocket accelerating upward 2) the observer in the rocket plastered to the floor of the rocket and 3) the ball remaining at the same position while the floor of the rocket moves upward to meet it. By contrast, the observer in the rocket feels like he’s being pulled down against the floor of the rocket in a manner identical to being pulled down toward the earth while standing on the earth’s surface. In addition, the observer in the rocket sees the ball fall from the ceiling to the floor at a rate identical to the rate it would fall from the same height to the surface of the earth.

From this, we can conclude – like Einstein did – that acceleration and gravity are the same thing.

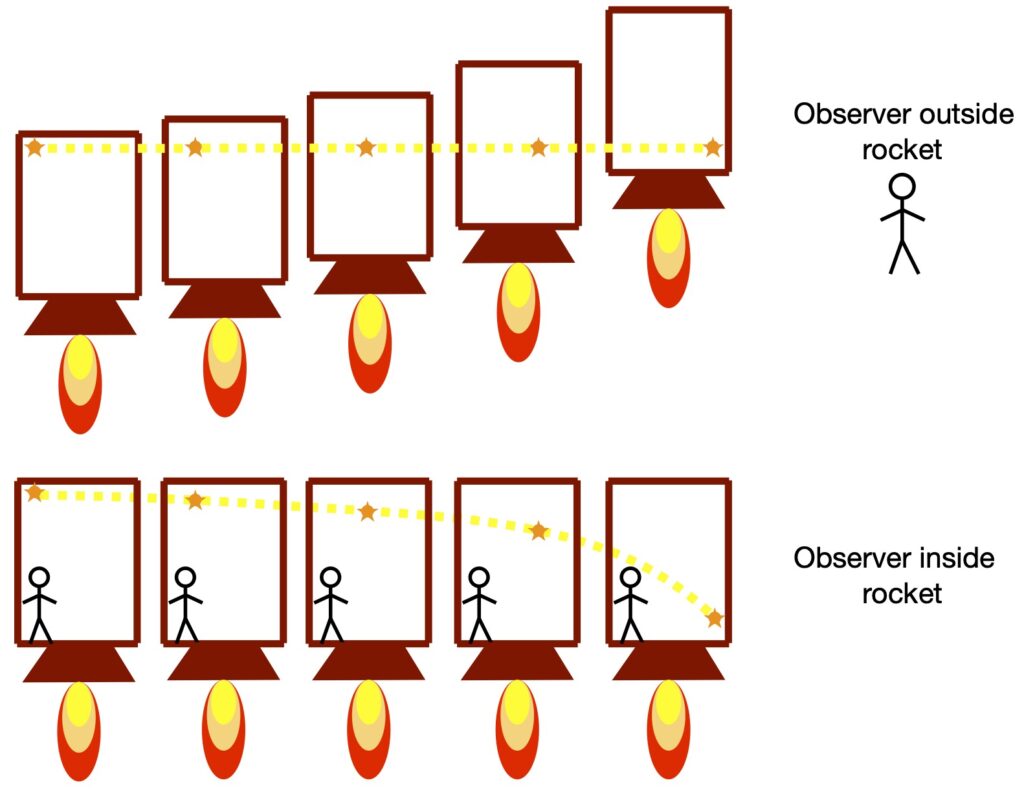

A similar phenomenon can be seen for light, as shown in figure I.A.3. In this figure, a light beam is shot in a rightward direction (let’s call it the x-direction) across an accelerating rocket. To an observer outside the rocket, the light beam appears to go straight across the rocket but the rocket’s floor gets increasingly close to the light beam as the rocket moves. On the other hand, an observer inside the rocket sees the light beam follow a parabolic path from the upper left to the lower righthand portion of the rocket. That is, the light gets “bent” in the accelerating frame of reference. And since Einstein considered acceleration and gravity to be equivalent, he concluded that gravity should “bend” light rays.

A more quantitative analysis of this problem yields further insight into what’s happening. In an inertial frame of reference, with the rocket moving in the z-direction with constant velocity, ![]() , relative to an observer outside the rocket, we can write the following equations:

, relative to an observer outside the rocket, we can write the following equations:

![]()

![]()

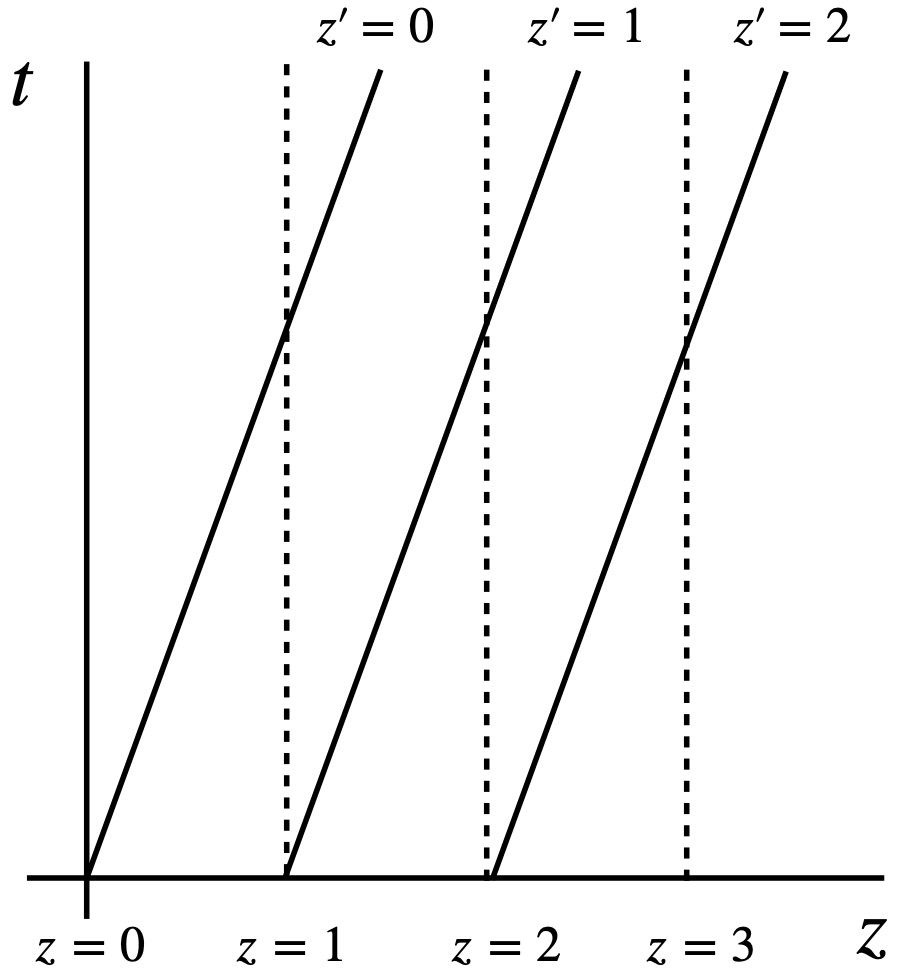

where the primed frame is that of an observer outside the rocket and the unprimed frame is that of an observer inside the rocket. Obviously, in special relativity, the expressions for spatial and time coordinate transformations would be more complex but this Newtonian view will suffice for our purposes here. We can also draw a spacetime diagram representing this inertial coordinate system, as in figure I.A.4.

The dotted lines represent the worldlines of objects within the rocket from the point of view of an observer in the rocket. Such an observer doesn’t thing he’s moving in space, thus worldlines in this frame of reference are straight vertical lines (i.e., the observer inside the rocket sees himself and objects inside the rocket as moving in time but not space). By contrast, the observer outside the rocket sees the rocket and its contents moving in both space and time. Worldlines for this observer are depicted as diagonal solid lines. Again the lines are straight.

Now let’s write equations for the accelerating rocket. Specifically, we’ll write Galilean transformation equations relating the primed coordinates of an observer outside the rocket and the unprimed coordinates of an observer inside the rocket:

![]()

![]()

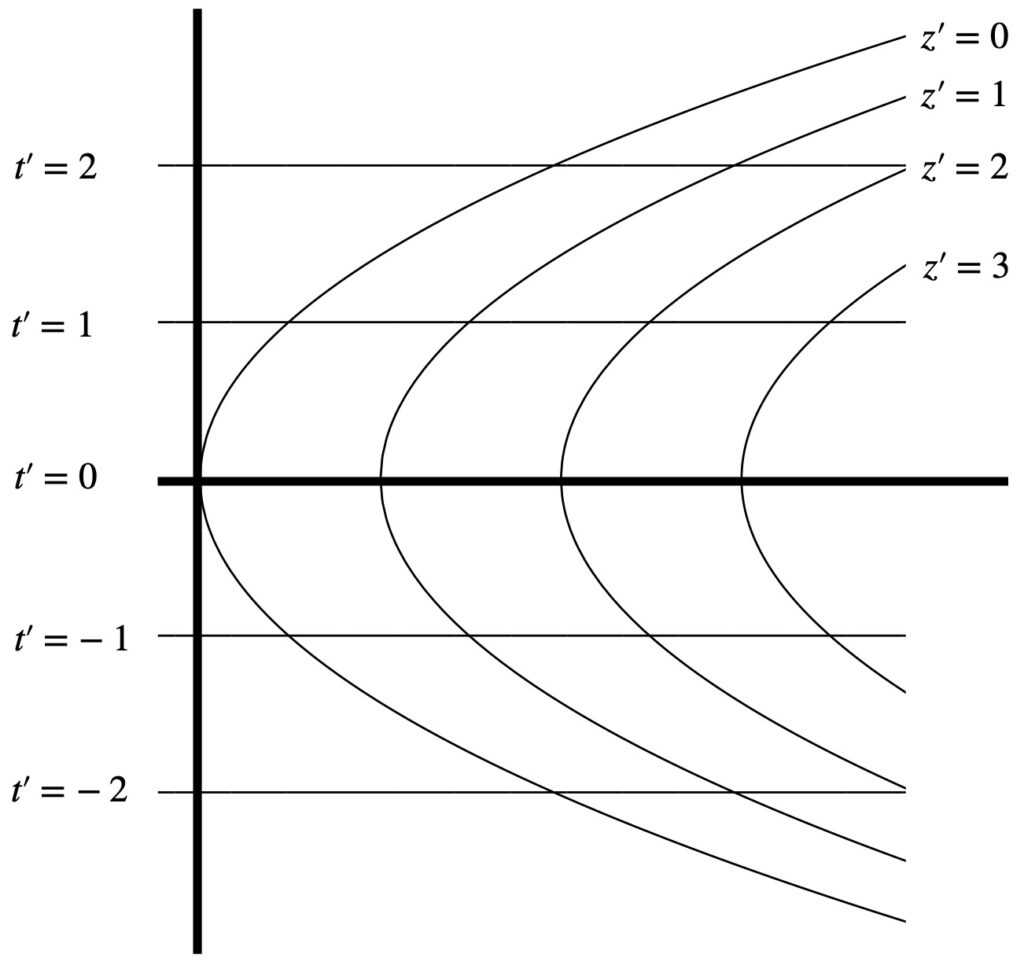

If we plot the primed coordinates on a spacetime diagram, we get something like this:

Instead of straight lines we get curved lines (i.e., parabolas) for the ![]() coordinates.

coordinates.

Furthermore, we can write a transformation equation for the light ray in an accelerating elevator. In this case, an observer outside the rocket is stationary, in the z-direction, with respect to the light beam. This observer would write the following equations:

![]()

![]()

The observer in the elevator, however, is accelerating with respect to the light beam in the z-direction. Because of this relative acceleration, we’ll consider this observer’s coordinates to be the primed coordinates. This observer would write:

![]()

![]()

That means that:

![]()

Plugging eq. (I.A.9) into eq. (I.A.8), we obtain:

![]()

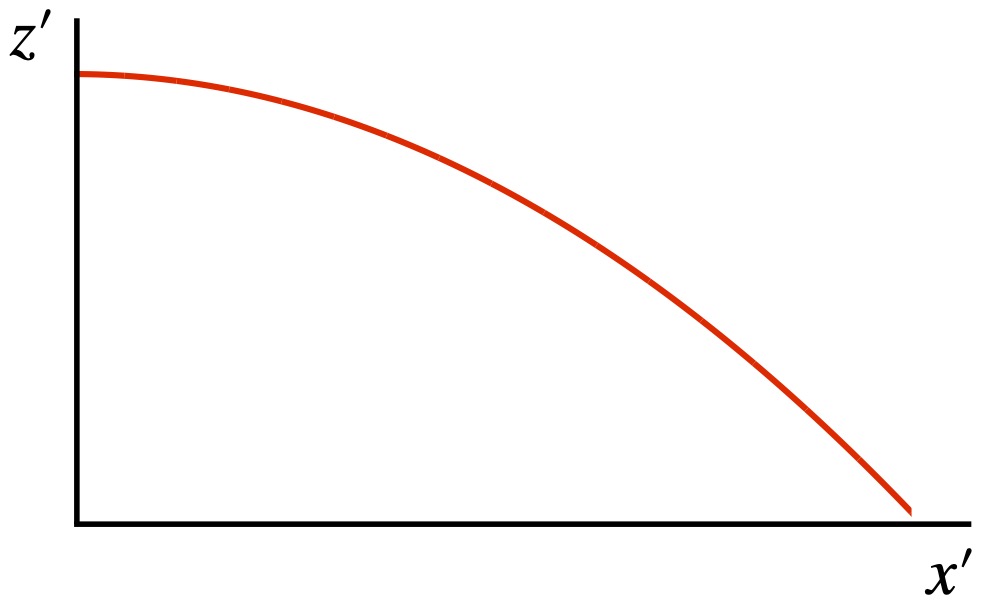

When we plot this equation, we get something like:

To Einstein, it was no coincidence that the path of light in an accelerated frame of reference and the coordinates in an accelerated frame are both curved in the same way (i.e., both are parabolas). Instead, it suggested to him that the light (or any other object for that matter) was simply following the shortest path along curved coordinates, coordinates that were the result of the acceleration. And because he presumed acceleration and gravity to be equivalent, he postulated that 1) gravity would also “bend” spacetime coordinates and 2) that light (and other objects) would follow these bent coordinates. Thus, it would appear that a massive object was exerting a gravitational force that was bending the light path (or the path of some other object), but really, the light (or the object) was just taking the shortest course it could along the bent coordinates. Such paths are referred to as geodesics; we will discuss them in greater detail later.

At any rate, Einstein developed these ideas further with another thought experiment. He imagined an observer (let’s call her observer A) at the center of a disc and another observer, observer B, at the outside of the disc. Across the diameter of the disc, we lay measuring rods. Let’s say it takes 10 of them to span the diameter of the disc. We also lay measuring rods around the circumference of the disc with the disc at rest with respect to the 2 observers. It takes 31.4 measuring rods to span the circumference of the disc.

Now we set the disc rotating. Each observer, in their own frame of reference – like any observer in their own frame of reference – sees themself at rest. However, observer A at the center of the rotating disc sees the observer B along the circumference of the disc as moving. From the theory of special relativity, we know that, to observer A, the measuring rods on the circumference of the disc undergo length contraction. Thus, it takes more than 31.4 measuring rods to span the circumference of the disc when the disc is in rotating motion relative to observer A. I don’t believe Einstein actually discussed this – in the context of this thought experiment – but per the theory of special relativity, to observer A, a clock on the circumference of the disc should tick slower than a clock at the center of the disc (i.e., time dilation takes place).

It has been noted that if such a disc were made of rigid material, it might break apart since, at each circumference level away from the disc center, differing degrees of circumferential length contraction should occur when the disc begins rotating while no length contraction should occur in the radial direction. Several solutions to this conundrum have been proposed in the literature such as, perhaps, the disc is made of malleable, fluid-like material or the disc is made of molten material which is allowed to cool only after the disc begins rotating. At any rate, this is a side argument that’s irrelevant to the point Einstein was trying to make.

Of course, observer B on the circumference of the rotating disc would also experience an outward (centrifugal) acceleration which would feel to him like gravity was pulling him outward. And since, in Einstein’s view, acceleration and gravity are equivalent, he reasoned that gravity should induce length contraction and time dilation as well.

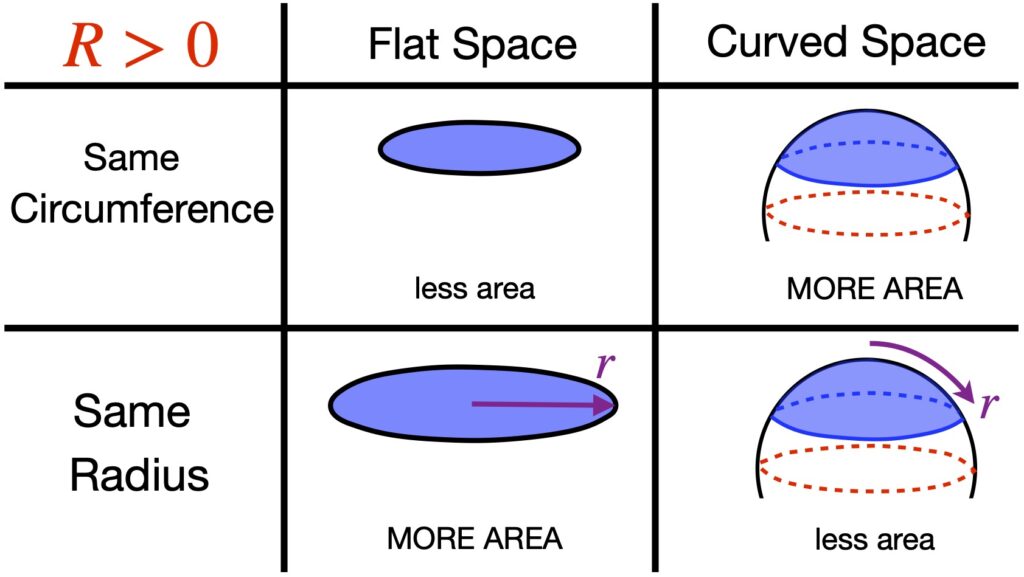

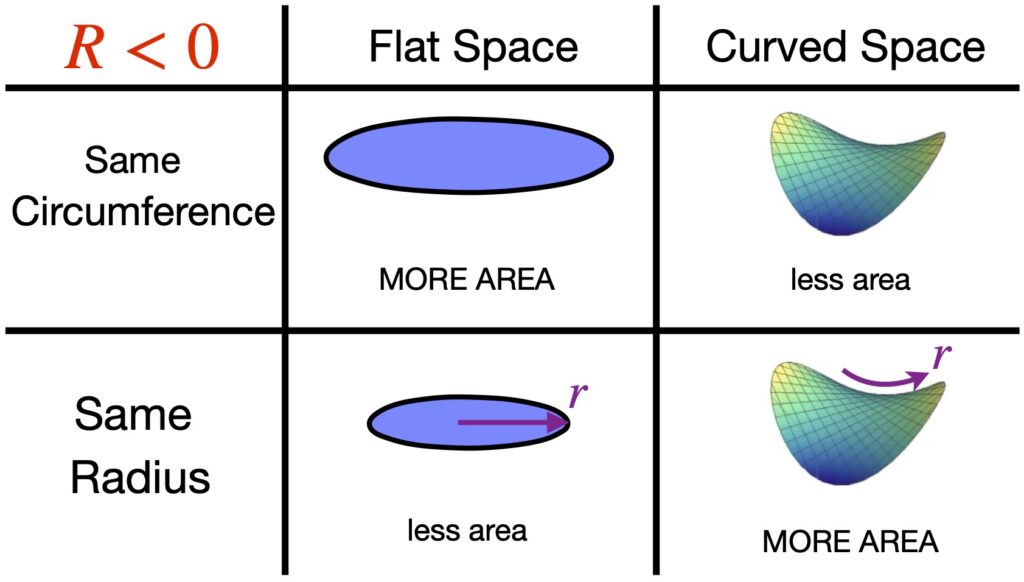

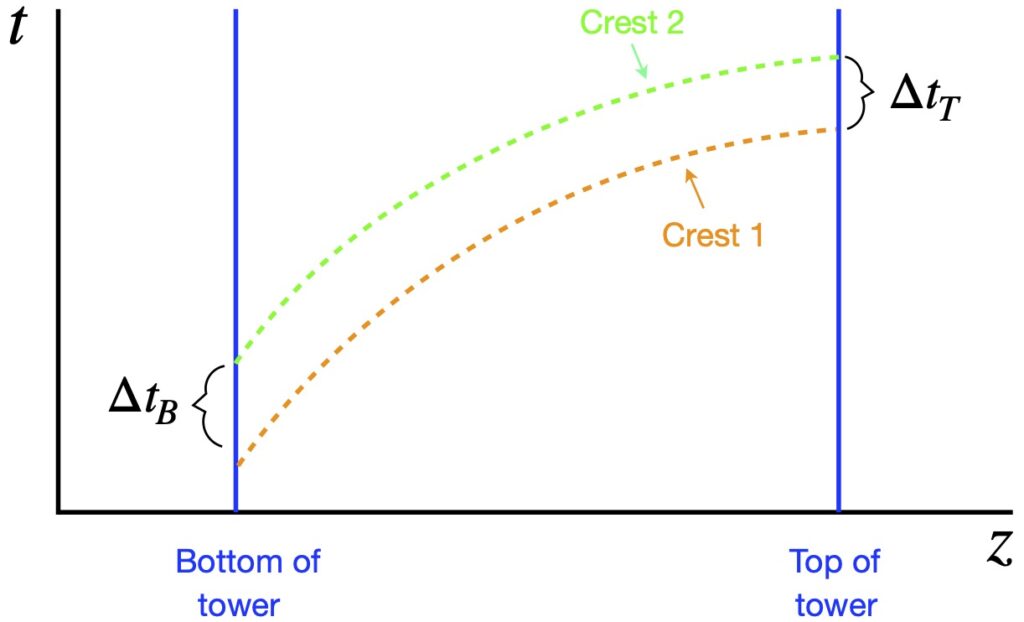

So we have this idea that gravity has something to do with spacetime geometry with balls and light rays following curved paths that resemble the curved worldlines one sees with accelerated reference frames. And we also have this notion that gravity appears to cause length contraction and time dilation. If you’re like I was, you may be wondering, What’s the link between length contraction/time dilation and curved spacetime. Figure 1.7 provides one way to visualize this relationship.

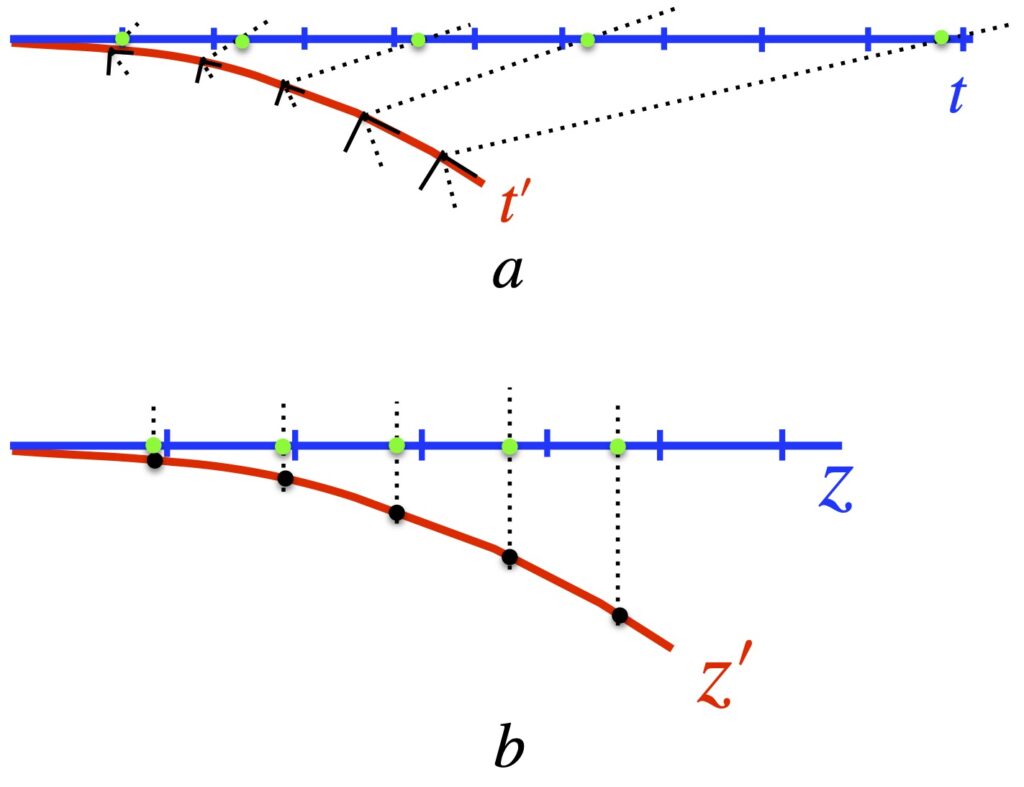

Figure I.A.7a, shows the time axes of 2 objects as seen by an observer very far away from a massive body. The blue time axis, ![]() , is that of the far away observer, and thus, measures proper time for that observer. The red time axis,

, is that of the far away observer, and thus, measures proper time for that observer. The red time axis, ![]() , corresponds to an object close to and moving toward the massive body, as seen by the far-away observer. An observer accompanying the object close to the massive body would – like any observer in their own frame of reference – think they aren’t moving. To this observer, each point in spacetime has, associated with it, a small set of coordinate axis which looks like flat (Minkowski) space (depicted in figure I.A.7a as little black axes at right angles to each other). The axes represent tiny local spacetime diagrams. The axis tangent to the red curve is the time axis. The axis perpendicular to the time axis is a spatial axis. In this setup, we’re only considering one spatial direction which we’ll call the z-axis. The dotted lines extending outward from the origin of each set of axes represent the path of light, oriented at 45°. The distance between the origin of each set of axes on the red time axis is equal to the tick marks on the blue axis, that distance representing 1 unit of time on both the blue and red axes. To see how the blue and red time axes relate to each other, an object moving along the red time axis sends out a light signal to the far-away observer from each set of axes, each pulse being – to the observer near the massive body – one time unit apart.

, corresponds to an object close to and moving toward the massive body, as seen by the far-away observer. An observer accompanying the object close to the massive body would – like any observer in their own frame of reference – think they aren’t moving. To this observer, each point in spacetime has, associated with it, a small set of coordinate axis which looks like flat (Minkowski) space (depicted in figure I.A.7a as little black axes at right angles to each other). The axes represent tiny local spacetime diagrams. The axis tangent to the red curve is the time axis. The axis perpendicular to the time axis is a spatial axis. In this setup, we’re only considering one spatial direction which we’ll call the z-axis. The dotted lines extending outward from the origin of each set of axes represent the path of light, oriented at 45°. The distance between the origin of each set of axes on the red time axis is equal to the tick marks on the blue axis, that distance representing 1 unit of time on both the blue and red axes. To see how the blue and red time axes relate to each other, an object moving along the red time axis sends out a light signal to the far-away observer from each set of axes, each pulse being – to the observer near the massive body – one time unit apart.

What time interval between these light pulses does the far-away observer detect? This is shown by the green dots at the intersection between the the path of the light rays (black dotted lines) and the blue time axis. What we see is that, as the object near the massive body gets closer to that body, the light signals it sends are detected by the far-away observer at time intervals that get farther and farther apart. If the path followed by the object close to the massive object had been straight, then the time intervals between light pulses would have been equally spaced, with length equal to the time intervals between the blue tick marks on the far-away observer’s time axis. Thus, we can see how time dilation can be thought of as a result of curved spacetime.

What about length contraction? This is addressed in figure 1.7b. In that figure, the blue axis (labeled ![]() ) is the spatial axis of an observer far from a massive body. The red curved axis (labeled

) is the spatial axis of an observer far from a massive body. The red curved axis (labeled ![]() is the spatial axis of an object moving toward a massive body, as seen by the far-away observer. Of course, an observer moving with the object near the massive body – like any observer in their own frame of reference – thinks they’re not moving. They see space as flat and see the length interval between points on their spatial axis as being equidistant, each 1 length unit apart, the same length as the blue tick marks on the far-away observer’s (blue) spatial axis. To communicate his position to the far-away observer, the observer near the massive body sends a light signal from each black dot, to the far-away observer. The light moves in a straight line to the far-away observer, being received by the far-away observer, on the blue axis, at the green dots. Whereas the observer near the massive body measures the distance between each black dot as 1 length unit, the far away observer sees the units of length as being less than one unit, with that length interval decreasing as the object close to the massive body gets closer to that source of mass. That is, the far-away observer experiences length contraction. If the spatial axis in the frame of reference of the object near the massive body had been straight, then the black dots on that spatial axis would have coincided exactly with the blue tick marks on the blue axis. Therefore, we can see how length contraction can be thought of as the result of curved spacetime.

is the spatial axis of an object moving toward a massive body, as seen by the far-away observer. Of course, an observer moving with the object near the massive body – like any observer in their own frame of reference – thinks they’re not moving. They see space as flat and see the length interval between points on their spatial axis as being equidistant, each 1 length unit apart, the same length as the blue tick marks on the far-away observer’s (blue) spatial axis. To communicate his position to the far-away observer, the observer near the massive body sends a light signal from each black dot, to the far-away observer. The light moves in a straight line to the far-away observer, being received by the far-away observer, on the blue axis, at the green dots. Whereas the observer near the massive body measures the distance between each black dot as 1 length unit, the far away observer sees the units of length as being less than one unit, with that length interval decreasing as the object close to the massive body gets closer to that source of mass. That is, the far-away observer experiences length contraction. If the spatial axis in the frame of reference of the object near the massive body had been straight, then the black dots on that spatial axis would have coincided exactly with the blue tick marks on the blue axis. Therefore, we can see how length contraction can be thought of as the result of curved spacetime.

So we can see how Einstein’s thought experiment about objects in free fall that led to the simple idea that inertial mass equals gravitational mass got the ball rolling toward a theory – general relativity – that revolutionized scientific thought. Before we move on, we should note that this simple idea has a name – the equivalence principle – and that this principle has been expressed in 3 forms:

- Weak Equivalence Principle: Over sufficiently small spacetime regions, the motion of freely falling objects due to gravity cannot be distinguished from uniform acceleration.

- Einstein Equivalence Principle: In sufficiently small regions of spacetime, we. can find a representation such that the laws of physics reduce to those of special relativity.

- Strong Equivalence Principle: Gravity is ultimately a form of energy, and as such, behaves like mass in a gravitational field.

We won’t talk much about the strong equivalence principle in this article. We’ve already discussed the weak equivalence principle in some detail . At this point, we need to say a few words about the Einstein equivalence principle, mainly because it will be a good lead-in to our next section.

To illustrate the Einstein equivalence principle, consider the rocket ship containing an observer and a ball we talked about earlier. If the observer and ball took on a frame of reference where they accelerated with same constant acceleration as the rocket, then the observer would no longer be plastered to the floor of the rocket and the ball would no longer fall. They would float weightlessly in the rocket like an observer and a ball in a rocket in inertial motion (relative to some observer watching both rockets) in far outer space, far away from any massive objects. We know the spacetime in such an inertial frame of reference is the spacetime of general relativity – Minkowski space. And because the observer and ball in the uniformly accelerating frame behave like the observer and ball and rocket in outer space, we can surmise that the spacetime governing the uniformly accelerating frame is also that of special relativity. Thus, a coordinate transformation has been found that has changed things from a uniformly accelerating frame with behavior that looks like motion due to gravity to one with behavior that looks like special relativity.

Another way of thinking about this is to consider the earth whose surface is spherical – clearly curved. However, if we look at a small patch of the earth, it looks flat to us. Similarly, in curved spacetime (like spacetime axes in the region of a massive object), if we examine a small enough region, it will look flat (analogous to the flat coordinate system of special relativity). For those who are interested, I’ll offer a detailed proof of this but I’ll have to defer this proof until I’ve introduced Christoffel symbols.

I.B Tidal Forces

At any rate, we keep saying that acceleration equals gravity and the laws of physics are equivalent to general relativity (which occurs in flat Minkowski space) “in sufficiently small regions of spacetime.” This is because, over larger areas where gravitational effects are in play, this is not true. These are called tidal effects (or tidal forces) and they will ultimately allow us to differentiate accelerated motion in flat space from accelerated motion due to gravity.

Renowned physicist Leonard Susskind, in his lecture series and book on general relativity, illustrates these effects by an example that he calls the 2000 mile man.

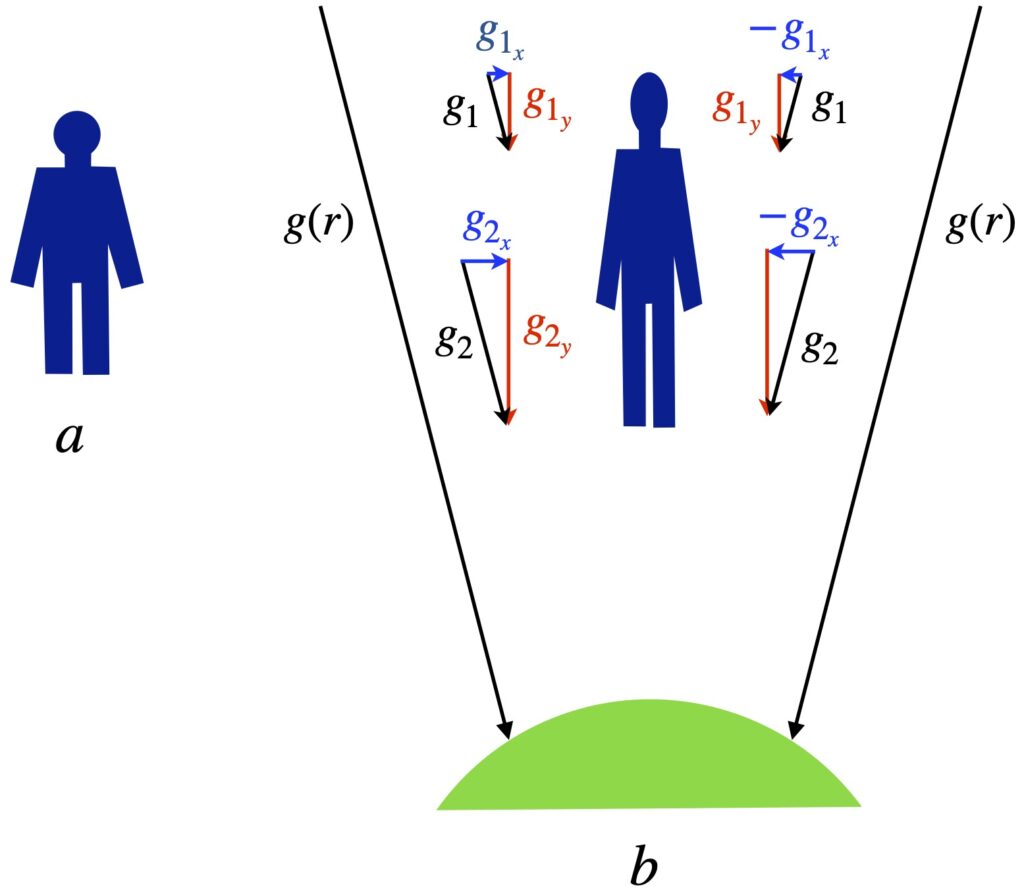

Figure 1.8a shows the 2000-mile-long man floating in space far from any massive body. Figure 1.8b shows the 2000-mile-long man near a massive body like the earth. Looking at things from a Newtonian point of view, the earth exerts a gravitational force, ![]() , on the man – a force that’s a function of the distance from the center of the earth.

, on the man – a force that’s a function of the distance from the center of the earth.

This gravitational force is oriented at an angle with respect to the long axis of the man. Thus, the man feels 2 components of force: one downward along his long axis and another directed inward toward his center. The latter inwardly directed forces squeeze him together. Meanwhile, the longitudinal forces vary from head to foot, the man experiencing a higher gravitational force near his feet (nearer the center of the earth) than at his head. This relative difference in longitudinal forces causes the man to stretch in the longitudinal direction.

When an accelerating frame of reference causes what appears to be a gravitational effect, we can always find a global coordinate transformation (i.e., a Lorentz transformation if we’re working in special relativity) that “gets rid” of the effects of gravity leading to a spacetime that looks flat.

On the other hand, this is impossible in a real gravitational field like that shown in figure 1.8. Why? Because the the gravitational field varies as a function of position, and thus, acceleration varies with position. If we try to make a global coordinate transformation that gets rid of the gravitational effect at one place (e.g., at the head of the 2000 mile man) then it won’t get rid of the gravitational effect in another place (e.g., at the feet of the 2000 mile man).

An even more extreme example would be to consider a person standing on the earth in Seville, Spain and another in Aukland, New Zealand, 2 locations separated by a straight line through the center of the earth. Both are influenced by earth’s gravity, but in opposite directions. Thus, if we make a global coordinate transformation that gets rid of the gravitational effect in Seville, it will double the gravitational effect in Aukland, and vice versa.

Einstein realized that frames of reference where there is no gravitational acceleration are equivalent to inertial frames of reference like the Minkowski space of special relativity, which we know is flat. By contrast, frames of reference where there is gravitational acceleration are associated with curved spacetime. We’ll defer proof of this until we acquire some additional mathematical tools, but for now, suffice it to say that we can always find a local coordinate transformation that makes a small region of curved spacetime flat. However, we can never identify a global coordinate transformation to make all of curved spacetime flat (proof ), and this inability to find such a global coordinate transformation is what tells us that a true gravitational effect (not just acceleration in flat space) and, thus, curved spacetime, is present.

How, then, can one determine whether true gravity/curved spacetime or acceleration in flat spacetime exists? Testing all possible coordinate transformations by trial and error could give us the answers but this, of course, is impractical. Einstein realized that he needed some novel method to make the differentiation. For this task, he turned to mathematician colleagues like Marcel Grossman who helped him find such a method: differential geometry. We’ll see how this helped to solve Einstein’s dilemma in the next section.

Curvature

Everything we do in this section is geared toward developing a mathematical method of differentiating flat spacetime from curved spacetime. However, this will involve several steps. To understand this process, the reader will need a basic understanding of tensors and Einstein summation notation. For those readers who need to learn about these topics, I have a tensors page on this website that gives an introduction to these subjects. There are several more comprehensive treatments on these topics elsewhere on the web. I list a few references to such sites in my tensors page. I’ll only provide an introduction to several of the topics I discuss in my tensor page but go into depth on topics I haven’t covered elsewhere.

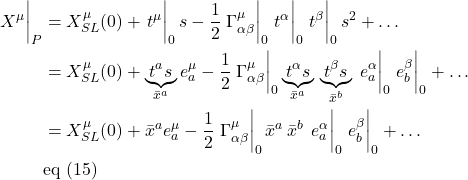

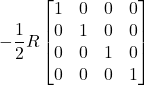

II.A Metric Tensor

We talked previously about Einstein’s thought experiment involving the rotating disc which showed how accelerating frames of reference, and thus gravity, can give rise to time dilation and length contraction. We then discussed how the variability in the magnitude of time and spatial units is related to curved spacetime. The metric tensor is what tells us the lengths of line elements, and therefore, the magnitude of the time and spatial units in spacetime.

Specifically, the length of a vector is given by the dot product with itself:

![]()

![]()

Suppose we have an infinitesimal displacement vector ![]() . To find its length,

. To find its length, ![]() , we take the dot product with itself:

, we take the dot product with itself:

![]()

![]()

![]()

To get the length, ![]() , we take the square root of eq. (II.A.2).

, we take the square root of eq. (II.A.2).

Notice that, in eq. (2.1.2), we’ve defined the entity ![]()

where, if we’re working in 2 dimensions, ![]() could be expressed as a matrix:

could be expressed as a matrix:

![]()

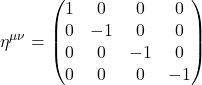

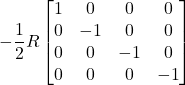

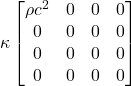

As it applies to physics, we can imagine that a tiny coordinate axis exists at every point in spacetime and that a metric exists at each point where the metric gives the relative lengths of the basis vectors in these infinitesimal coordinate systems. In flat spacetime, the metric is the same everywhere. An example is the spacetime of special relativity, Minkowski space, where the metric is the same at every point and is given by:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \eta = \begin{bmatrix} -1&0&0&0 \\ 0&1&0&0 \\ 0&0&1&0 \\ 0&0&0&1 \end{bmatrix} \quad \text{or} \quad \begin{bmatrix} 1&0&0&0 \\ 0&-1&0&0 \\ 0&0&-1&0 \\ 0&0&0&-1 \end{bmatrix} \quad \text{eq. (II.A.4)} \]](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-26cd87b51660f0493fd32a74f71ee90f_l3.png)

In curved spacetime, this is not the case. The metric varies from point to point. This might cause one to wonder, Is calculation of the metric a way to check to see if spacetime is flat? (i.e., if the metric is the same everywhere, the space is flat; if not, it isn’t). It turns out that we can always find a set of coordinates where ![]() and

and ![]() (i.e., where the metric is not changing to first order. However, if the space is curved, we can never find a coordinate system where

(i.e., where the metric is not changing to first order. However, if the space is curved, we can never find a coordinate system where ![]() . A proof of this can be found :

. A proof of this can be found :

Thus, we can’t use the metric alone to determine whether or not a space is flat. As we’ll see later, to do this, we’ll have to come up with a mathematic object that incorporates the second derivative of the metric.

There are a few properties of the metric that we should briefly mention here:

- The metric tensor is a symmetric tensor.

- The covariant derivative of the metric tensor is zero:

.

. - The metric tensor can be used to raise and lower indices on tensors. For example:

.

.

II.B Covariant Derivative

The first topic we need to touch upon on our way to understanding curvature is the covariant derivative. Briefly, if we are working in Cartesian coordinates, we can take derivatives and partial derivative in the manner that’s taught in undergraduate calculus classes i.e., by taking the derivative of vector components. This works because, in Cartesian coordinates, basis vectors are the same everywhere. However, in non-Cartesian coordinates in flat spacetime (e.g., non-orthogonal axes, Minkowski spacetime), basis vectors are not constant. The problem is even more severe in curved spacetime where basis vectors vary from point to point. We want our derivative operation to return a tensor, because the laws of physics should be invariant in all frames of reference, and the only way that this can happen is if we use tensor equations to describe them. And the only way to return a tensor from our derivative operation is to take basis vectors into account.

Let’s look at a vector

![]()

where

![]() are the components of the vector

are the components of the vector

![]() are the basis vectors

are the basis vectors

If we want to take the derivative of this vector ![]() , since both the components and basis vectors can vary, we need to use the chain rule:

, since both the components and basis vectors can vary, we need to use the chain rule:

![]()

![]()

The result, referred to as the covariant derivative, is a tensor.

II.C Christoffel Symbols

The righthand-most term in eq. II.B.2 is frequently expressed in the following way:

![]()

And so, eq. II.B.2 becomes:

![]()

Changing some indices and rearranging, we get:

![]()

The term in parentheses is called the covariant derivative:

![]()

It represents the component of the derivative of vector ![]() in the

in the ![]() direction and – as opposed to Christoffel symbols alone – it is a tensor.

direction and – as opposed to Christoffel symbols alone – it is a tensor.

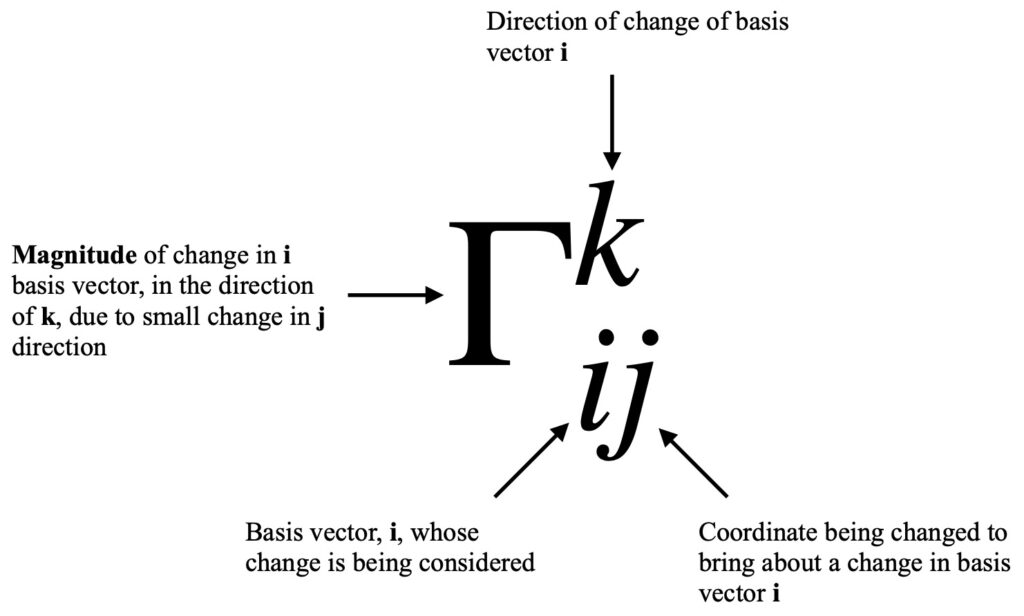

The meaning of the Christoffel symbol is shown in figure II.C.1.

There are 2 types of Christoffel symbols, depending on how they’re expressed in terms of the metric. Christoffel symbols of the first type are written as:

![]()

Christoffel symbols of the second type are written as:

![]()

Derivations of eq. (II.C.6) can be found here:

It’s the Christoffel symbols of the second type, the one most often used in general relativity, that we’ll be using in this article.

It should be noted that the Christoffel symbol is a kind of connection coefficient. There are many ways we can define connection coefficients. The Christoffel symbol of the second type, as defined above, is also called the Levi-Civita connection.

II.D Parallel Transport

We would expect that, to take the covariant derivative in a curved space, we could simply take the difference between 2 vectors, ![]() and

and ![]() , separated by a short distance,

, separated by a short distance, ![]() , then take the limit as

, then take the limit as ![]() goes to zero:

goes to zero:

![]()

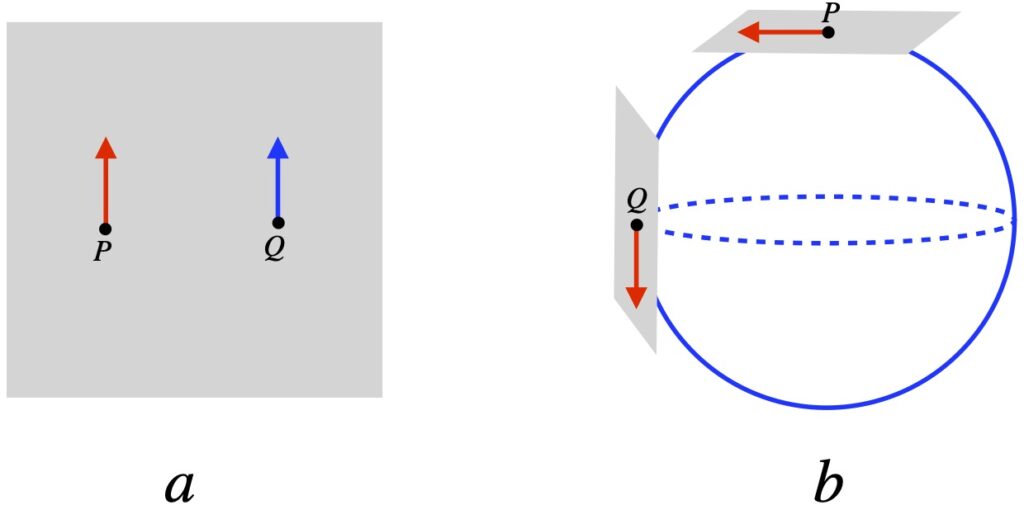

However, we can’t do this because ![]() is undefined. This is due to the fact that, in order to compare 2 vectors, they have to be in the same tangent plane. But the tangent spaces at points P and Q in a curved space are not the same, as shown in figure II.D.1.

is undefined. This is due to the fact that, in order to compare 2 vectors, they have to be in the same tangent plane. But the tangent spaces at points P and Q in a curved space are not the same, as shown in figure II.D.1.

We can show this algebraically as well. We know we can express vectors as a sum of components and basis vectors:

![]()

In flat space, we can write the quantity ![]() as:

as:

![]()

Because, in flat space, the tangent space and basis vectors are the same everywhere, we have ![]() . Therefore:

. Therefore:

![]()

and we can subtract components in the numerator of our expression for the derivative in eq. (II.D.1).

However, if coordinates are curved, basis vectors (and in the case of curved space, tangent planes) aren’t the same at the points P and Q. Thus, we can’t just subtract components in the numerator of the expression for the derivative.

In order to compare 2 vectors in curved space, we need to transport one vector to the tangent space of the other vector, then compare them. How do we transport them? By a process called parallel transport.

What does it mean to parallel transport a vector? In words, it means “as we progress along a path (e.g., worldline or coordinate line), keep the vector parallel to itself.” This translates, in mathematical terms, to “the covariant derivative of the vector, in the direction of the tangent vector, is zero” which means that, when we move along the tangent vector (i.e., move along a worldline or other parameterized curve because the tangent vector is everywhere parallel to the curve), the vector does not change. The equation that expresses this idea is:

![]()

where

![]()

In pictorial form:

In figure II.D.2a, we see parallel transport in flat space. The vector just points in the same direction at every point along a closed loop and it ends up pointing in the same direction that it started at the apex of the loop.

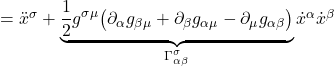

In figure II.D.2b, we see parallel transport in a curved space, the surface of a sphere. The way we can visual this is to imagine that the vector we’re parallel transporting is a spear being held by a person walking along the curve. He starts at the top of the closed curve and walks along the curve with the spear pointing along the direction he’s walking. When he reaches the equator, the curve he is traversing courses to the right. In an attempt to keep the spear pointing in the same direction, the person keeps the spear pointing down (the same direction it was pointing when it reached the equator). To do this, he walks sideways and rightward. At the point where the curve courses upward from the equator, again, keeping the spear pointing down, the person carrying the spear keeps it pointing down but walks backward. As he walks backward, the spear remains in the tangent plane but the tangent plane gets “tilted backward” as he walks. When he reaches the starting point, at the apex of the curve, the spear (i.e., the orange vector) remains in the tangent plane (as it does all along the curve) except that it points in a direction different from that in which it pointed at the start of its journey (green vector). Thus, despite “trying to keep the spear (vector) parallel” as it was transported around the closed loop, when it reaches the origin of the trip, the spear (vector) points in a different direction that in which it started because the direction of the basis vectors changed as the curve was traversed.

I go through this little exercise here because parallel transport will play a central role in understanding geodesics and the Riemann tensor, the ultimate tool we’ll us to determine spacetime curvature.

II.E Lie Derivative

Lie transport is an alternative way to look at transporting vectors and gives rise to the Lie derivative, Lie bracket, Killing vector fields and spacetime symmetries. While these topics are useful for advanced applications in general relativity, they aren’t immediately important for what I’m covering in this article. However, in my first go-round in learning general relativity, I admit I was befuddled by Lie derivatives and their associated topics so I’ve decided to discuss them here, largely to enhance my own understanding. Because they are a bit of an aside, I’ll provide links which can be clicked to see the information on these subjects, if the reader so desires.

II.E.1 Derivation

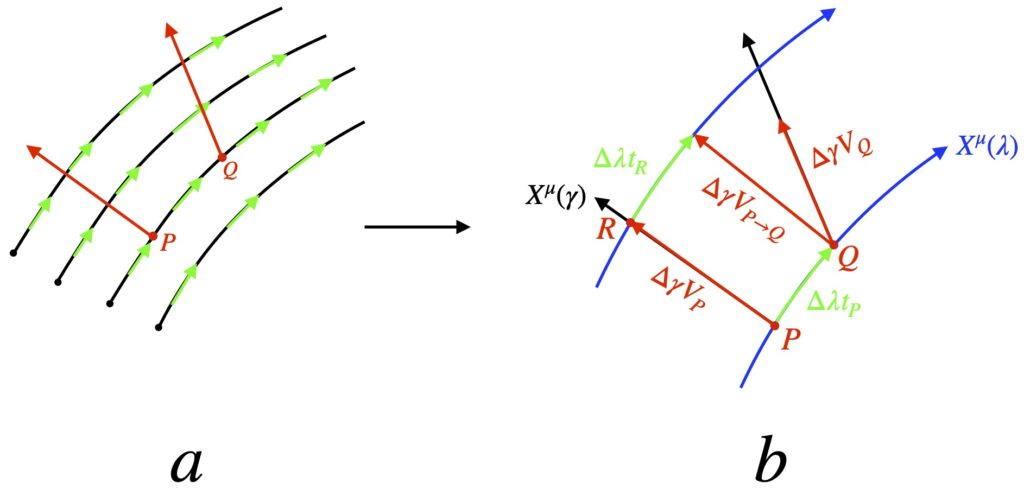

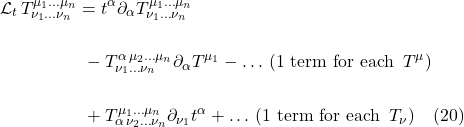

In the covariant derivative, we use parallel transport to transport one vector to another so they can be compared. The mathematical object that facilitates this transport is the Christoffel symbol which is a function of the metric. But there are other ways to transport vectors so they can be compared. One is Lie transport. A vector undergoing Lie transport follows the “flow” of integral curves created by a vector field. The comparison it allows is called the Lie derivative. Figure 1 depicts Lie transport along integral curves and defines the quantities we will need to find the Lie derivative.

As shown in figure 1a, we start with a vector field with tangent vectors (shown in green) that can be connected to constitute integral curves (also called flow lines). Figure 1b shows a small section of the vector field noted in figure 1a with tangent vectors (green), ![]() , along 2 integral curves (blue) parameterized by a variable

, along 2 integral curves (blue) parameterized by a variable ![]() with coordinates

with coordinates ![]() .

.

We define a displacement vector, oriented along an integral curve parameterized by the variable ![]() , pointing in a direction defined by coordinates

, pointing in a direction defined by coordinates ![]() , with tangent vector

, with tangent vector ![]() . The displacement vector extends from point P to point R, point R lying along one of

. The displacement vector extends from point P to point R, point R lying along one of ![]() vector field flow lines. Its length is

vector field flow lines. Its length is ![]() (which is what we’ll call this vector).

(which is what we’ll call this vector).

We define another displacement vector along another flow line of vector field ![]() with tangent vector

with tangent vector ![]() . This displacement vector starts at point Q and has length

. This displacement vector starts at point Q and has length ![]() so we’ll call it

so we’ll call it ![]() .

.

We define a third displacement vector from point P to point Q along the tangent vector between the 2 points, ![]() . Its length is

. Its length is ![]() and we’ll call it

and we’ll call it ![]() .

.

Finally, we construct a fourth displacement vector along the upper ![]() flow line, beginning at point R and extending a distance

flow line, beginning at point R and extending a distance ![]() along the tangent vector,

along the tangent vector, ![]() , on that flow line. We’ll call this displacement vector

, on that flow line. We’ll call this displacement vector ![]() .

.

We now transport vector ![]() to point Q, dragging its base along

to point Q, dragging its base along ![]() to point Q, its tip ending up at the tip of

to point Q, its tip ending up at the tip of ![]() . This is called Lie transport. We’ll call this transported vector

. This is called Lie transport. We’ll call this transported vector ![]() .

.

Now we subtract ![]() from

from ![]() to get the Lie derivative.

to get the Lie derivative.

Let’s make this a bit more mathematically precise.

First, ![]() , the tangent vectors along the

, the tangent vectors along the ![]() and

and ![]() flow lines can be expressed as a differential operator:

flow lines can be expressed as a differential operator:

![]()

The components of ![]() are:

are:

![]()

That means that:

![]()

Now we define the Lie derivative as:

![]()

where, for the time being, we’ll use ![]() to refer to the Lie derivative.

to refer to the Lie derivative.

Next, we multiply both sides of eq. (4) by ![]() . We get:

. We get:

![]()

We know that we the components of a displacement vector are just the difference between its coordinates at its tip and its tail. So:

![]()

![]()

Let’s look at the ![]() component of eq. (5):

component of eq. (5):

![]()

Let’s examine the term ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

![]()

![]()

and

![]()

![]()

We put the results of eq. (8) and eq. (9) back into eq. (7) and obtain:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We can cancel ![]() ‘s and

‘s and ![]() ‘s leaving us with:

‘s leaving us with:

![]()

and ultimately:

![]()

In arriving at eq. (10), we drop the ![]() subscripts since we’ve taken the limit as

subscripts since we’ve taken the limit as ![]() goes to zero meaning the points

goes to zero meaning the points ![]() and

and ![]() essentially coincide.

essentially coincide.

The Lie derivative is usually denoted by ![]() . So we have:

. So we have:

![]()

which denotes the ![]() component of the Lie derivative of

component of the Lie derivative of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() .

.

II.E.2 Other Lie Derivatives

II.E.2.a Lie Derivative of a Scalar

![]()

II.E.2.a Lie Derivative of a (0,1) Tensor

We know that when a (0,1) tensor (i.e., a covector) acts on a vector, we get a scalar, so we have:

![]()

We know how the Lie derivative acts on a scalar, so we get:

![]()

Applying the product rule to the Lie derivative gives us:

![]()

We know how to take the Lie derivative of a vector i.e., a (1,0) tensor. Thus, eq. (14) becomes:

![]()

We expand the righthand side of eq. (13) using the product rule. This yields:

![]()

When we equate the righthand sides of eq. (15) and eq. (16), we obtain:

![]()

![]()

We want to cancel the term ![]() on both sides. To do this, we rename dummy indices in the righthand term on the righthand side of eq. (18):

on both sides. To do this, we rename dummy indices in the righthand term on the righthand side of eq. (18):

![]()

![]()

Doing this gives us:

![]()

After making these cancellations, we are left with:

![]()

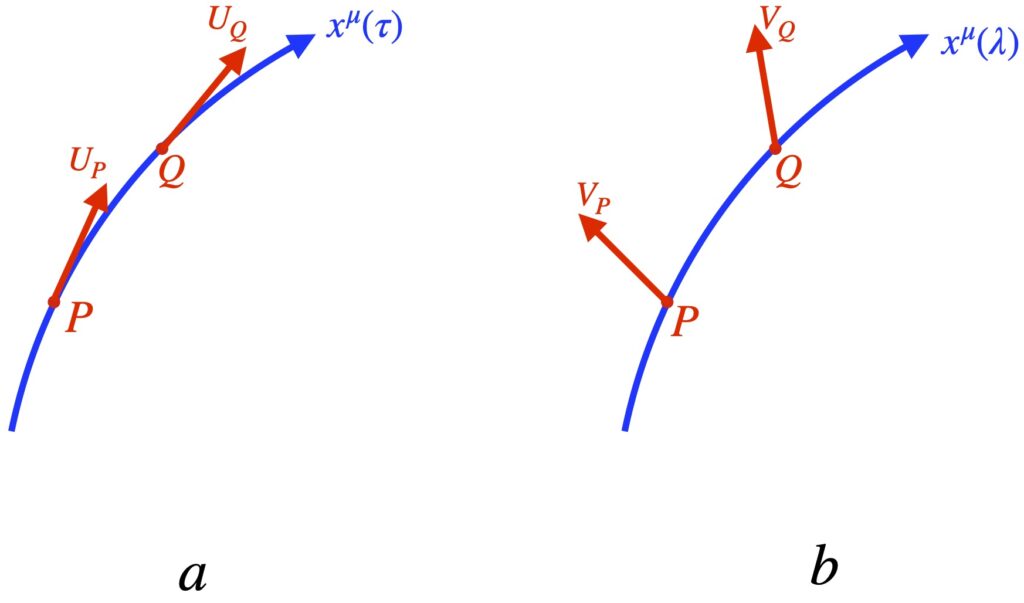

II.E.2.c Lie Derivative of (n,m) Tensor

We can generalize the expression of the Lie derivative to tensors of any rank as follows:

Let ![]() be a tensor of rank

be a tensor of rank ![]() . Then the Lie derivative is:

. Then the Lie derivative is:

III.E.3 Spacetime Symmetries

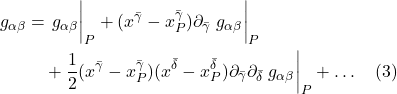

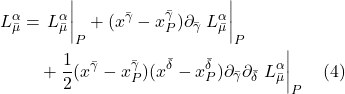

In figure X, we have integral curves, ![]() (shown in blue) of a vector field

(shown in blue) of a vector field ![]() . What we mean by spacetime symmetry is that all of the points along the flow lines of the vector field remain separated by the same spacetime distance. That means that, if there is spacetime symmetry, then the spacetime separations between the points separated by

. What we mean by spacetime symmetry is that all of the points along the flow lines of the vector field remain separated by the same spacetime distance. That means that, if there is spacetime symmetry, then the spacetime separations between the points separated by ![]() and

and ![]() are equal. That is:

are equal. That is:

![]()

We expand each of the terms on the righthand side of eq. (2) in a Taylor series to first order:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

All of the ![]() terms raised to powers of

terms raised to powers of ![]() are negligible and can be ignored. Thus, we have:

are negligible and can be ignored. Thus, we have:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We can divide through by ![]() to obtain:

to obtain:

![]()

![]()

Next, we rename some dummy indices. Specifically, in the first term on the lefthand side, we change ![]() ; in the second term on the lefthand side, change

; in the second term on the lefthand side, change ![]() . That gives us:

. That gives us:

![]()

![]()

This allows us to divide through by ![]() . When we do this and rearrange, we are left with:

. When we do this and rearrange, we are left with:

![]()

But we recognize eq. (6) as the Lie derivative of the metric along the vector field ![]() :

:

![]()

What this means is that spacetime is symmetric along the integral curves of a vector field ![]() if

if ![]() . And the vector field

. And the vector field ![]() that defines this symmetry is called a Killing vector field.

that defines this symmetry is called a Killing vector field.

Now let’s examine an important consequence of these findings. Consider what happens if one of the coordinate basis vectors is a Killing vector field. Suppose, for example, that the ![]() coordinate basis vectors are a Killing vector field. The basis vector along the flow lines that make up the

coordinate basis vectors are a Killing vector field. The basis vector along the flow lines that make up the ![]() field is given by

field is given by ![]() . The fact that the

. The fact that the ![]() field is a Killing vector field means that

field is a Killing vector field means that ![]() . Expanding this out, we get:

. Expanding this out, we get:

![]()

The Killing vector field consists of just the ![]() flow lines so we can say:

flow lines so we can say:

![]()

Because ![]() is a constant, the terms in eq. (8) with

is a constant, the terms in eq. (8) with ![]() in them become zero. The first term in eq. (8) becomes

in them become zero. The first term in eq. (8) becomes ![]()

This tells us that, if one of the metric components is independent of one of the coordinates (i.e., its derivative is zero which means it doesn’t change), then 1) the vector field that defines that coordinate is a Killing vector field and 2) the spacetime is symmetric under translations along those coordinate lines. Such symmetry under translations along a coordinate line can indicate the presence of conservation laws. For example, if the time coordinate is shown to be a Killing vector field, then there is time translation symmetry which indicates the presence of energy conservation.

Note, however, that if ![]() components are not independent of any coordinates, this does not imply that there are no symmetries. There may well be a symmetry, just not along a coordinate line.

components are not independent of any coordinates, this does not imply that there are no symmetries. There may well be a symmetry, just not along a coordinate line.

III.E.4 Lie Bracket

Another way to express the Lie derivative is the Lie bracket. This discussion is drawn, in part, from the YouTube video from eigenchris, Tensor Calculus 21: Lie Bracket, Flow, Torsion Tensor. Figure 1 shows how the two are analogous. Figure 1a, taken from figure Xb, shows, diagrammatically, the Lie derivative. Figure 1b, patterned after the eigenchris video, depicts the Lie bracket.

The Lie bracket can be defined as:

![]()

where ![]() , is the commutator of

, is the commutator of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We can expand out the first term on the lefthand side of eq. (1):

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Next, we expand out the second term on the lefthand side of eq. (1):

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Now we subtract eq. (3) from eq. (2):

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We can compare eq. (4) with the expression for the Lie derivative given in eq. (11):

![]()

![]()

The similarities are obvious.

It’s certainly not a proof but the following is interesting to note nonetheless:

![]() and

and ![]()

This implies:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() is, of course, a commutator, just like the Lie bracket.

is, of course, a commutator, just like the Lie bracket.

III.E.5 Torsion Tensor

Using what we learned about the Lie bracket, we can now use it to introduce the torsion tensor. The torsion tensor is defined as:

![]()

where

![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() parallel transported along

parallel transported along ![]()

![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() parallel transported along

parallel transported along ![]()

![]() is the Lie bracket of

is the Lie bracket of ![]() and

and ![]()

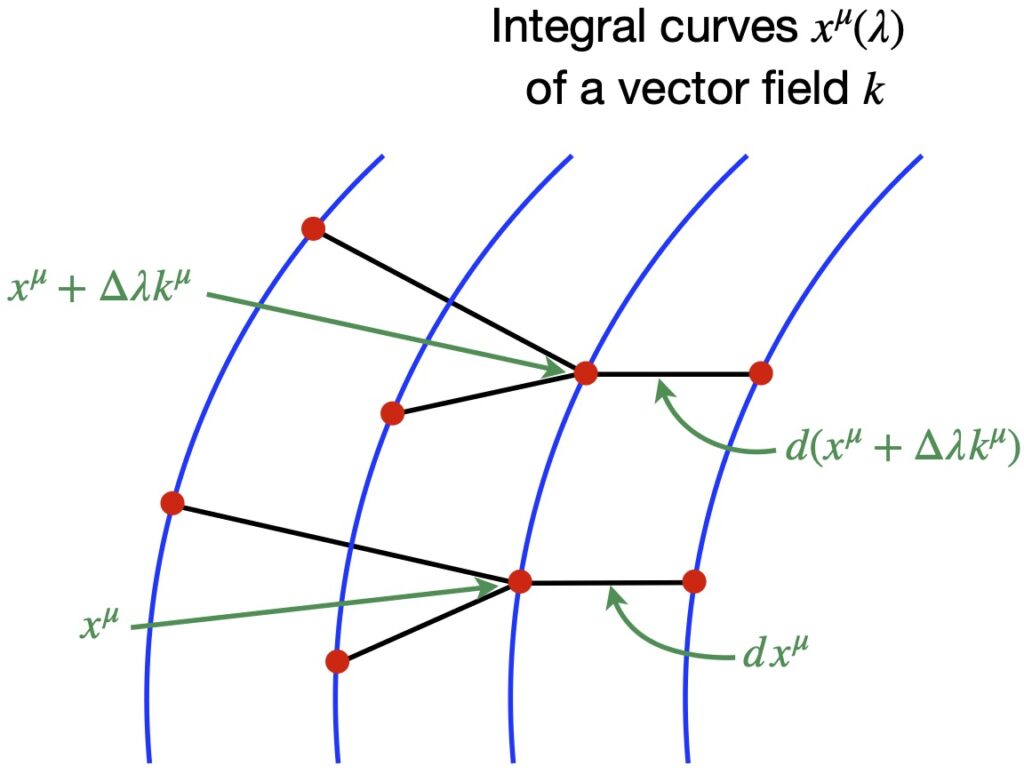

Recall that parallel transport involves moving a vector along a curve keeping it “as straight as possible.” The connection coefficient or Christoffel symbol helps define this motion. In Lie transport, a vector is “swept along” the flow line (or integral curve) of a vector field. Figure 1 shows the difference and gives a geometric interpretation of the torsion tensor.

Figure 1a represents vectors that are part of vector fields ![]() (shown in blue) and

(shown in blue) and ![]() (shown in red). The vector

(shown in red). The vector ![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() which has been parallel transported from point P to point Q. Similarly, the vector

which has been parallel transported from point P to point Q. Similarly, the vector ![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() which has been parallel transported from point P to point R. The difference between them is the torsion tensor

which has been parallel transported from point P to point R. The difference between them is the torsion tensor ![]() .

.

In figure 1a, ![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() which has been Lie transported from P to Q. And

which has been Lie transported from P to Q. And ![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() after it’s been Lie transported from P to R. The difference between these 2 vectors, shown in purple, is the Lie bracket

after it’s been Lie transported from P to R. The difference between these 2 vectors, shown in purple, is the Lie bracket ![]()

In the last 2 paragraphs and moving forward in this section, I’ve dropped the arrow above the letter notation since the context makes it clear that we’re dealing with vectors.

Figure 1b is a visual depiction of eq. (1). We start with the magenta vector labeled ![]() which represents the difference between the parallel transported vector

which represents the difference between the parallel transported vector ![]() and

and ![]() , a quantity given by the covariant derivative (as suggested by the label). We subtract from that the difference between

, a quantity given by the covariant derivative (as suggested by the label). We subtract from that the difference between ![]() and

and ![]() which, again, is the covariant derivative

which, again, is the covariant derivative ![]() (represented by the cyan vector.) Next we subtract the Lie bracket (represented by the purple vector.) The result is the torsion tensor

(represented by the cyan vector.) Next we subtract the Lie bracket (represented by the purple vector.) The result is the torsion tensor ![]() , shown in black. The torsion tensor is an operator that takes in 2 vectors and yields as its product a vector representing the difference between the 2 vectors parallel transported along each other.

, shown in black. The torsion tensor is an operator that takes in 2 vectors and yields as its product a vector representing the difference between the 2 vectors parallel transported along each other.

If we set the torsion tensor to zero, that means the separation between the parallel transported vectors is zero which means we get a closed 4-sided shape, as shown in figure 2.

Image

Mathematically:

![]()

![]()

When the above condition holds for all vector fields, we say the the connection is “torsion free.” It’s important to note, before going forward, that when we talk about torsion, we’re talking about the nature of the connection coefficients (e.g. Christoffel symbols.) It does not depend on the vector fields.

Now let’s find the components of the torsion tensor.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} T(u,v) &= \nabla_{\vec{u}} \vec{v} -\nabla_{\vec{v}} \vec{u} - \bigl[\vec{u}, \vec{v}\bigr] \\ \\ &= \nabla_{\vec{u}} \vec{v} -\nabla_{\vec{v}} \vec{u} -\Bigl( \vec{u}(\vec{v}) - \vec{v}(\vec{u}) \Bigr) \\ \\ &=u^i \bigl( \partial _i v^k + v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \bigr) \partial_k - v^i \bigl( \partial _i u^k + u^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \bigr) \partial_k \\ &\quad - \biggl[ \Bigl[ u^i \partial_i \bigl( v^j \partial_j \bigr) \Bigr] - \Bigl[ v^i \partial_i \bigl( u^j \partial_j \bigr) \Bigr] \biggr] \\ \\ &= u^i \bigl( \partial _i v^k + v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \bigr) \partial_k - v^i \bigl( \partial _i u^k + u^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \bigr) \partial_k \\ &\quad - \biggl[ \Bigl[ u^i (\partial_i v^j)\partial_j + \cancel{u^iv^j(\partial_i\partial_j)} \Bigr] - \Bigl[ v^i (\partial_i u^j)\partial_j + \cancel{v^i u^j(\partial_i\partial_j)} \Bigr] \biggr]\\ \\ &= \bigl(u^i \partial _i v^k \partial_k + u^i v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k \bigr) - \bigl( v^i \partial _i u^k \partial_k + v^i u^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k \bigr) \\ &\quad - \biggl[ u^i (\partial_i v^j)\partial_j - v^i (\partial_i u^j)\partial_j \biggr] \\ \\ &= \bigl( \cancel{u^i \partial _i v^k \partial_k} + u^i v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k \bigr) - \bigl( \bcancel{v^i \partial _i u^k \partial_k} + v^i u^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k \bigr) \\ &\quad - \cancel{\biggl[ u^i (\partial_i v^k)\partial_k} - \bcancel{v^i (\partial_i u^k)\partial_k} \biggr] \\ \\ &= u^i v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k - v^i u^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k \\ \\ &= u^i v^j \Gamma^{k}_{ij} \partial_k - v^j u^i \Gamma^{k}_{ji} \partial_k \\ \\ &= u^i v^j \Bigl( \Gamma^{k}_{ij} - \Gamma^{k}_{ji} \bigr) \partial_k \quad \text{(3)} \end{align*}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ed5148b476a5940f6da6273ef9a31602_l3.png)

The term in parentheses are the components of the torsion tensor:

![]()

When the torsion tensor is zero, ![]() . Thus, the lower indices of the Christoffel symbols can be freely interchanged.

. Thus, the lower indices of the Christoffel symbols can be freely interchanged.

Eq. (4) also proves what we stated previously: namely, that the torsion tensor depends only on the connection coefficients, not on the coordinates.

II.F Geodesics

We’ve noted previously that, in an accelerated reference frame, and thus, in a gravitational field, light is predicted to follow a curved course. In fact, all objects tend to move along a path that’s as straight as possible (if not influenced by a non gravitational force), but in curved spacetime (like in a gravitational field), that path may be curved. Such motion is the general relativity version of Newton’s first law. Indeed, the natural state of motion of objects is said to be free fall, like that of the observer in the elevator plummeting toward earth, described in the introduction section.

We can formalize this mathematically in 2 ways:

II.F.1 Method 1

Since geodesic motion is the motion of free fall, and an observer in free fall experiences no acceleration, any mathematical description of such motion must include the fact that acceleration is zero. Accordingly, we need to start by coming up with a tensor expression for acceleration.

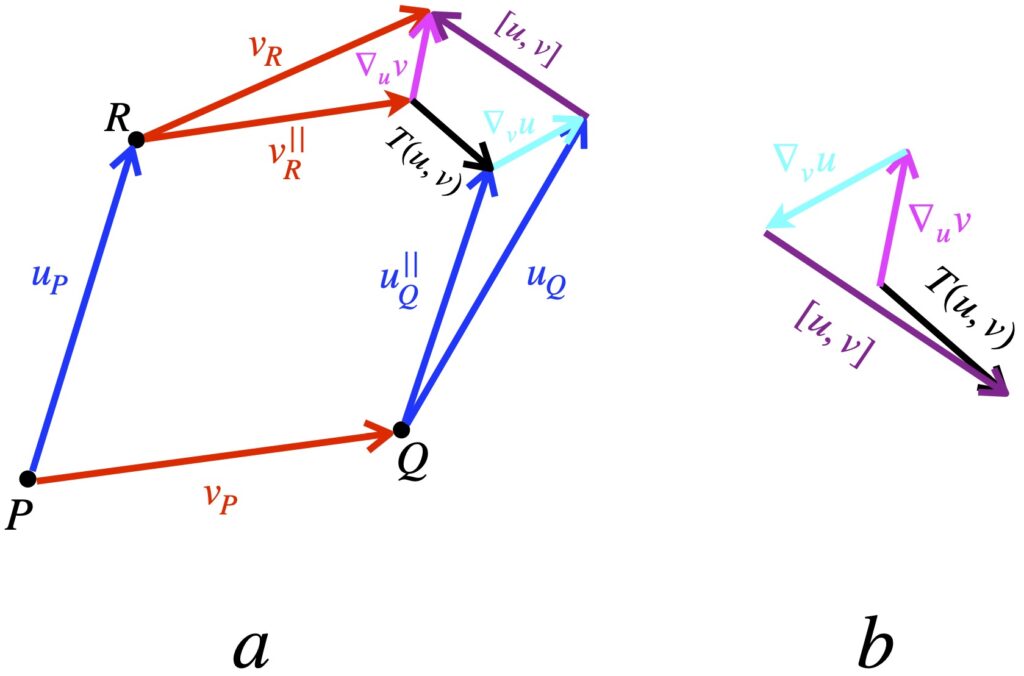

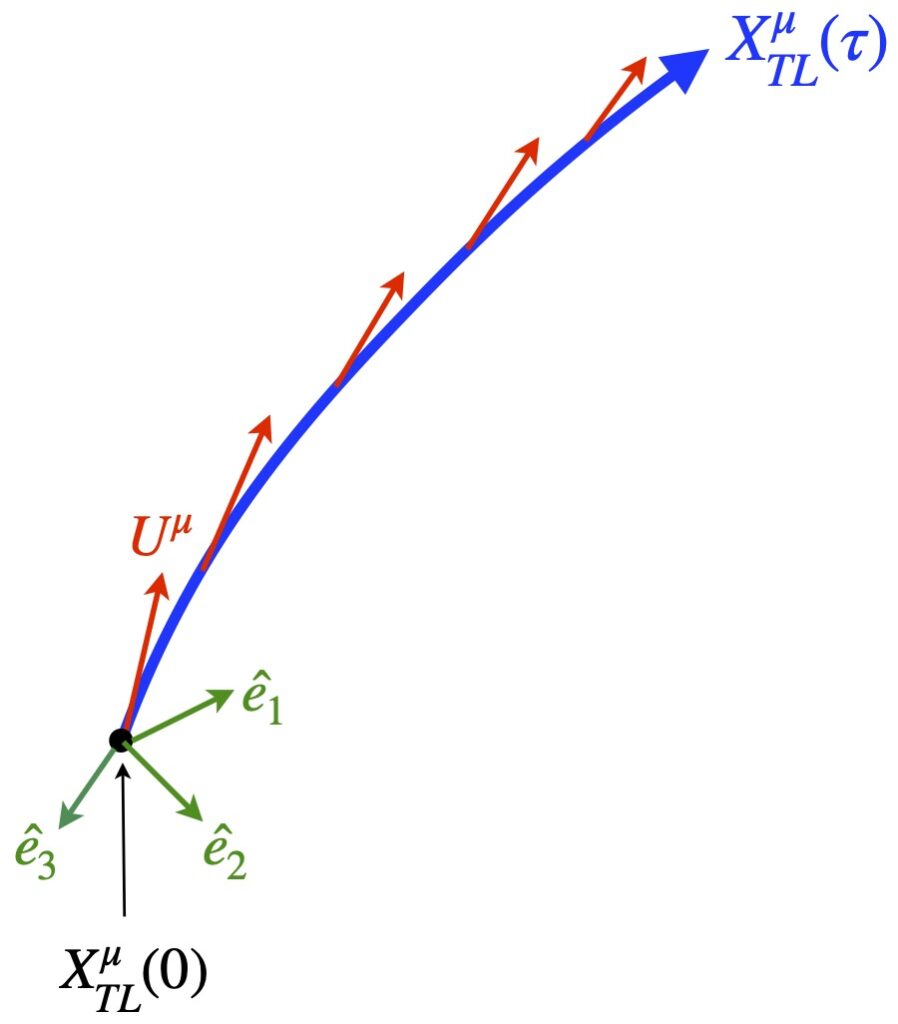

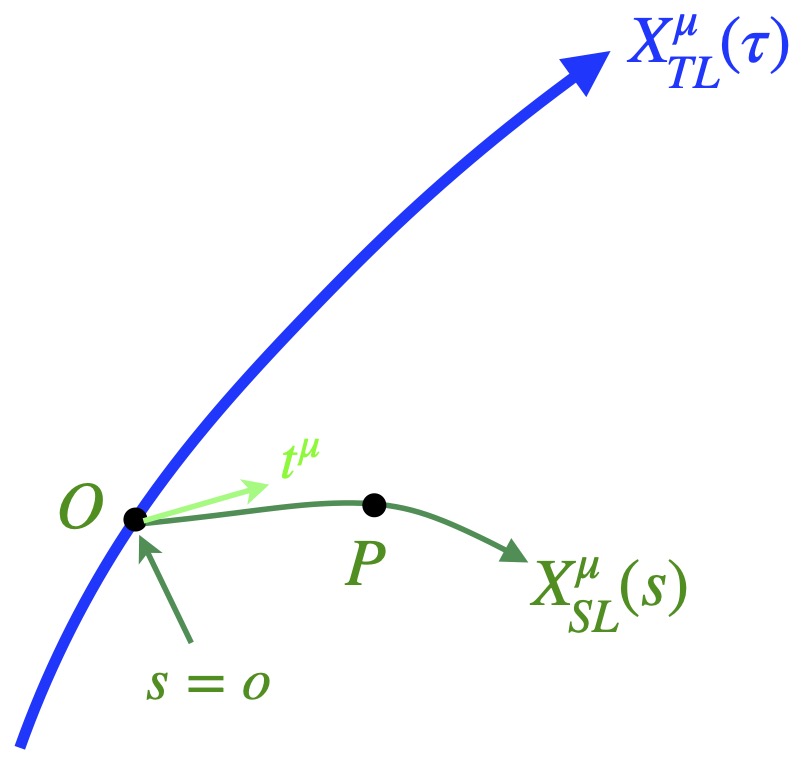

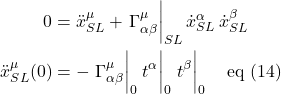

Referring to figure 2.5.1a, we can write a tensorial expression for acceleration as follows:

![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() are velocity vectors on a worldline

are velocity vectors on a worldline ![]() is geodesic parameterized by

is geodesic parameterized by ![]() . Of course, velocity vectors are tangent vectors, and like all vectors, can be thought of as a derivative operator, in this case

. Of course, velocity vectors are tangent vectors, and like all vectors, can be thought of as a derivative operator, in this case ![]() .

. ![]() represents the vector

represents the vector ![]() parallel transported to point P so that a meaningful covariant derivative can be taken.

parallel transported to point P so that a meaningful covariant derivative can be taken.

We’ve seen previously how to, in general, take a covariant derivative. Referring to figure 2.5.1b, we take ![]() and parallel transport it from point Q to point P on a worldline parameterized by

and parallel transport it from point Q to point P on a worldline parameterized by ![]() , then us the following equation:

, then us the following equation:

![]()

The components of the covariant derivative ![]() , then, are :

, then, are :

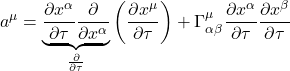

![]()

where

![]()

![]()

![]()

Making the analogies ![]() and

and ![]() , we come up with the following tensor equation for the components of the acceleration:

, we come up with the following tensor equation for the components of the acceleration:

![]()

![]()

Now, ![]() . Therefore:

. Therefore:

![]()

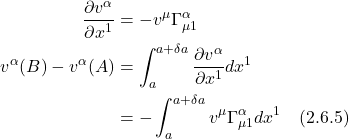

Since when traveling along a geodesic, there is no acceleration, we set eq. (2.5.6) to zero. We get:

![]()

Eq. (2.5.7) is called the geodesic equation. This equation, in this form, applies to a timelike geodesic. If we were dealing with a spacelike geodesic, we’d replace ![]() with

with ![]() . Lightlike geodesics are a little trickier. To write a valid geodesic equation for a lightlike geodesic, we’d use 4-momentum instead of 4-velocity in our equation as well as a parameter

. Lightlike geodesics are a little trickier. To write a valid geodesic equation for a lightlike geodesic, we’d use 4-momentum instead of 4-velocity in our equation as well as a parameter ![]() where

where ![]() ,

, ![]() being mass. We take the limits

being mass. We take the limits ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() remaining constant. For a more detailed explanation of the geodesic equation for lightlike geodesics, I refer you to

remaining constant. For a more detailed explanation of the geodesic equation for lightlike geodesics, I refer you to

II.F.2 Method 2

This derivation is taken from Physics Unsimplified.

This second method of deriving the geodesic equation borrows the principle of stationary action from Lagrangian mechanics.

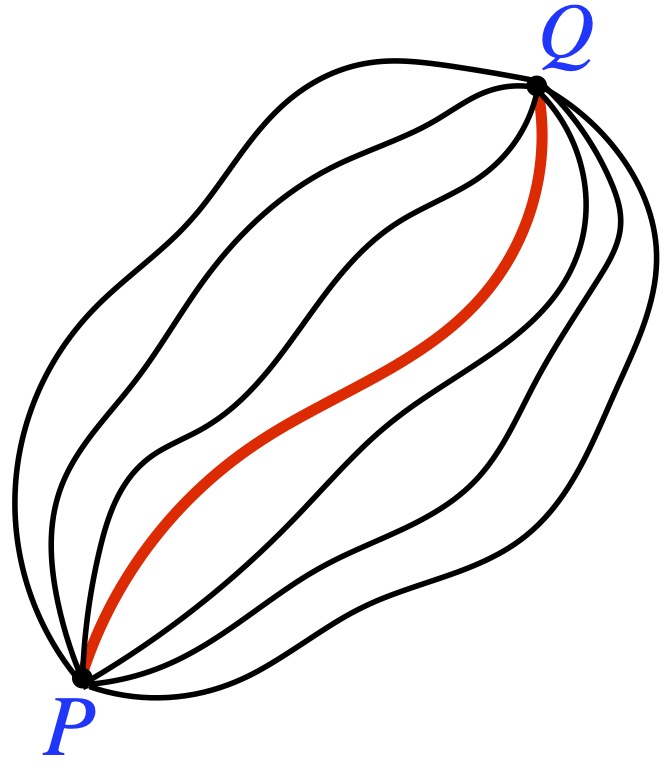

We imagine 2 points in spacetime, P and Q. There are an infinite number of possible paths, parameterized by some variable (say ![]() – proper time), that the particle could take in moving from P to Q. The path that the particle actually takes is the one that extremalizes the distance between P and Q,

– proper time), that the particle could take in moving from P to Q. The path that the particle actually takes is the one that extremalizes the distance between P and Q, ![]() . More information on this process and Lagrangian mechanics, in general, can be found here. We can apply this technique to arrive at the geodesic equation.

. More information on this process and Lagrangian mechanics, in general, can be found here. We can apply this technique to arrive at the geodesic equation.

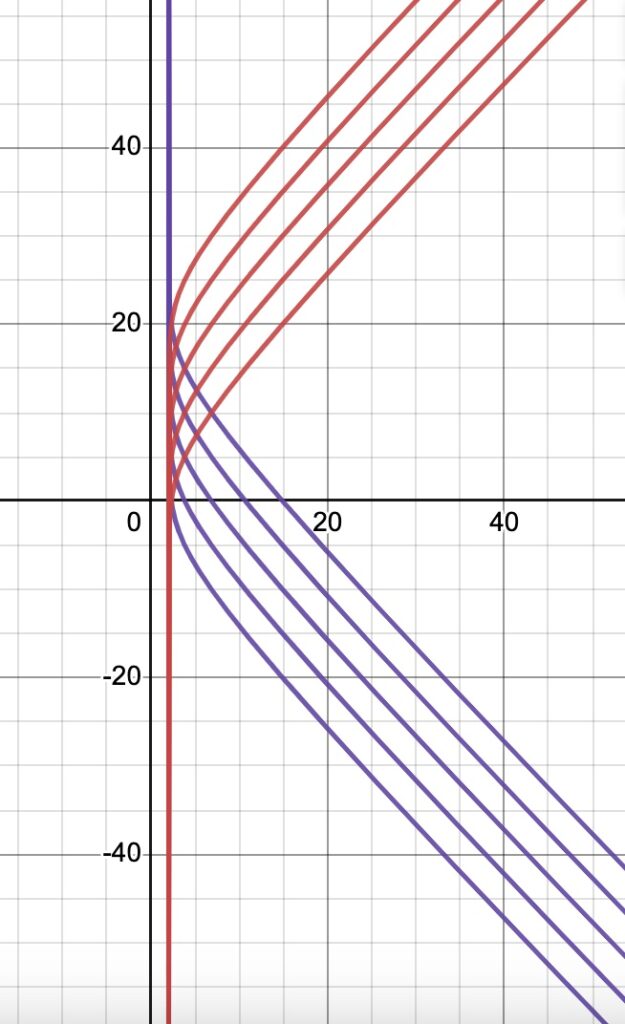

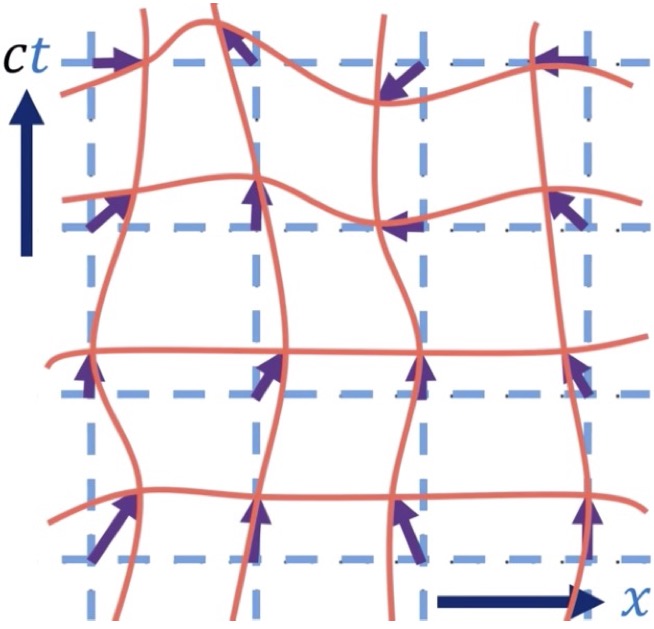

Figure 2.5.2 shows several worldlines – parameterized by ![]() – that a particle could follow between the points P and Q. The red worldline is the actual path taken by the particle (although we don’t know that before we start). The worldlines in the diagram are meant to be timelike but some, from the way they’re drawn, appear spacelike. Please excuse the deficiencies in my artwork. At any rate, we want to find the path that minimizes or maximizes the proper time it takes to traverse the path. We know that:

– that a particle could follow between the points P and Q. The red worldline is the actual path taken by the particle (although we don’t know that before we start). The worldlines in the diagram are meant to be timelike but some, from the way they’re drawn, appear spacelike. Please excuse the deficiencies in my artwork. At any rate, we want to find the path that minimizes or maximizes the proper time it takes to traverse the path. We know that:

![]()

The worldlines are given by ![]() . The velocity vectors (which are the tangent vectors) are given by

. The velocity vectors (which are the tangent vectors) are given by ![]()

Now

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Placing the results of eq. (2.5.10) into eq. (2.5.8), we get:

![]()

Next, we want to examine all of the possible paths by varying ![]() slightly, add up all the changes and see what the effect is on

slightly, add up all the changes and see what the effect is on ![]() . The path that results in a minimum or maximum of

. The path that results in a minimum or maximum of ![]() – and the equation that describes that path – is the one that’s “picked out” by the process. It’s known that finding the minimum or maximum value of a function occurs when the first derivative is zero. Likewise, the extremal value of

– and the equation that describes that path – is the one that’s “picked out” by the process. It’s known that finding the minimum or maximum value of a function occurs when the first derivative is zero. Likewise, the extremal value of ![]() can be found when

can be found when ![]() . So the equation we need to solve is:

. So the equation we need to solve is:

![]()

Differentiating using the product rule, we have:

![]()

![]()

But ![]()

Using this relationship in eq. (2.5.13), we get:

![]()

Next, we integrate by parts. The following is a brief recap of how integration by parts works.

![]()

![]()

![]()

In our case:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Applying integration by parts to the term ![]() , we obtain:

, we obtain:

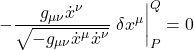

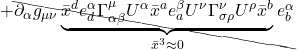

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle \delta \tau = -\displaystyle \frac{g_{\mu \nu}\dot{x}^{\nu}}{\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \eval{\delta x^{\mu}}_P^Q + \int_P^Q d\lambda \biggl[ \frac{d}{d\lambda}\left( \frac{g_{\mu \nu}\dot{x}^{\nu}}{\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \right) \delta x^{\mu} - \frac{\partial_{\alpha} g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}{2\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \delta x^{\alpha} \biggr] \quad \text{(2.5.16)}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bcc9b5bfbdc88cc47685986860f243d9_l3.png)

Points P and Q are fixed; they don’t vary. Thus, ![]() . Therefore the term

. Therefore the term  . This makes eq. (2.5.16):

. This makes eq. (2.5.16):

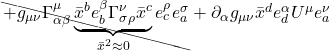

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle \delta \tau = \int_P^Q d\lambda \biggl[ \frac{d}{d\lambda}\left( \frac{g_{\mu \nu}\dot{x}^{\nu}}{\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \right) \delta x^{\mu} - \frac{\partial_{\alpha} g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}{2\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \delta x^{\alpha} \biggr] \quad \text{(2.5.17)}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3a10c2527928c528dd308ccc89dff39f_l3.png)

We’d like to factor out the ![]() terms but they have different indices. We can fix this by making the following dummy index changes in the righthand term:

terms but they have different indices. We can fix this by making the following dummy index changes in the righthand term: ![]() and

and ![]() . That gives us:

. That gives us:

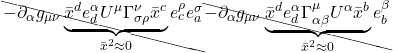

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \displaystyle \delta \tau = \int_P^Q d\lambda \biggl[ \frac{d}{d\lambda}\left( \frac{g_{\mu \nu}\dot{x}^{\nu}}{\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \right) - \frac{\partial_{\mu} g_{\alpha \beta} \dot{x}^{\alpha} \dot{x}^{\beta}}{2\sqrt{-g_{\mu \nu} \dot{x}^{\mu} \dot{x}^{\nu}}}} \delta x^{\mu} \biggr] \delta x^{\mu} \quad \text{(2.5.18)}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d09356effd26281358eebd0bceb68197_l3.png)

We want to extremize the proper time so we set ![]() . The only way this can happen is if the term in bracket is zero. That yields:

. The only way this can happen is if the term in bracket is zero. That yields:

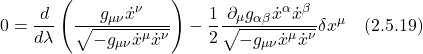

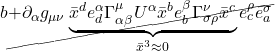

Eq. (2.5.19) is true for any arbitrary parameter lambda. Thus, it still holds if we set ![]() . When we do this, the

. When we do this, the ![]() terms become

terms become ![]() where

where ![]() represents the 4-velocity. But we know that the dot product of the 4-velocity is -1 (in units where c=1). Thus:

represents the 4-velocity. But we know that the dot product of the 4-velocity is -1 (in units where c=1). Thus:

![]()

When we substitute this result into eq. (2.5.19), eq. (2.5.19) becomes:

![]()

![]()

Multiplying both sides of eq. (2.5.20) by ![]() changes eq. (2.5.20) to:

changes eq. (2.5.20) to:

![]()

We’d like to factor out a factor of ![]() from the righthand term of eq. (2.5.21). To do this, we have to change the dummy index

from the righthand term of eq. (2.5.21). To do this, we have to change the dummy index ![]() in the lefthand term in the parentheses. We have:

in the lefthand term in the parentheses. We have:

![]()

Because ![]() is symmetric in their indices, this means that

is symmetric in their indices, this means that ![]() so we can replace the term

so we can replace the term ![]() with the expression

with the expression ![]() . We get:

. We get:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Eq. (2.5.23), of course, is the geodesic equation, which is what we were trying to derive.

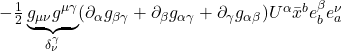

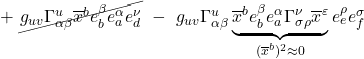

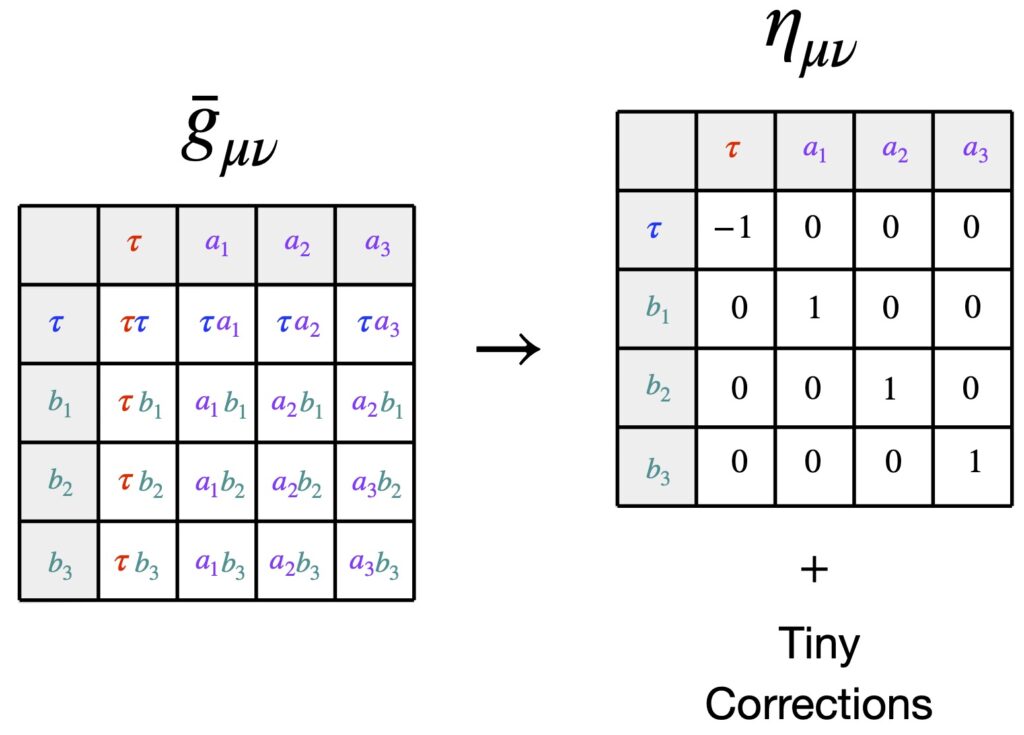

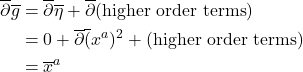

Local Inertial Frame

I mentioned earlier that, even in curved spacetime, spacetime, over small regions, spacetime looks flat. And I said that I’d offer a proof later. Now, with some additional mathematical tools in our toolkit, I’m in a position to provide that proof.

The above statement – that in small regions, spacetime will look flat – can also be expressed in the following manner: For each tiny region in spacetime, coordinates can be chosen such that the observed metric is the Minkowski metric (i.e., spacetime appears flat). Such coordinates are called Fermi normal coordinates. Proof of this is tedious. However, for those interested, a proof of this can be found .

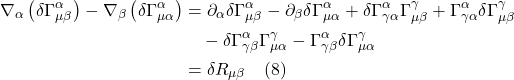

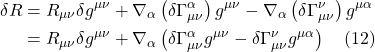

Riemann Curvature Tensor

With the concepts of the covariant derivative and parallel transport in hand, we’re now ready to find a method for determining whether a space is flat or curved.

Derivation

The derivation that follows is taken from Robert Davies, “Riemann Curvature Tensor” which is part of his Tensor Calculus series on YouTube.

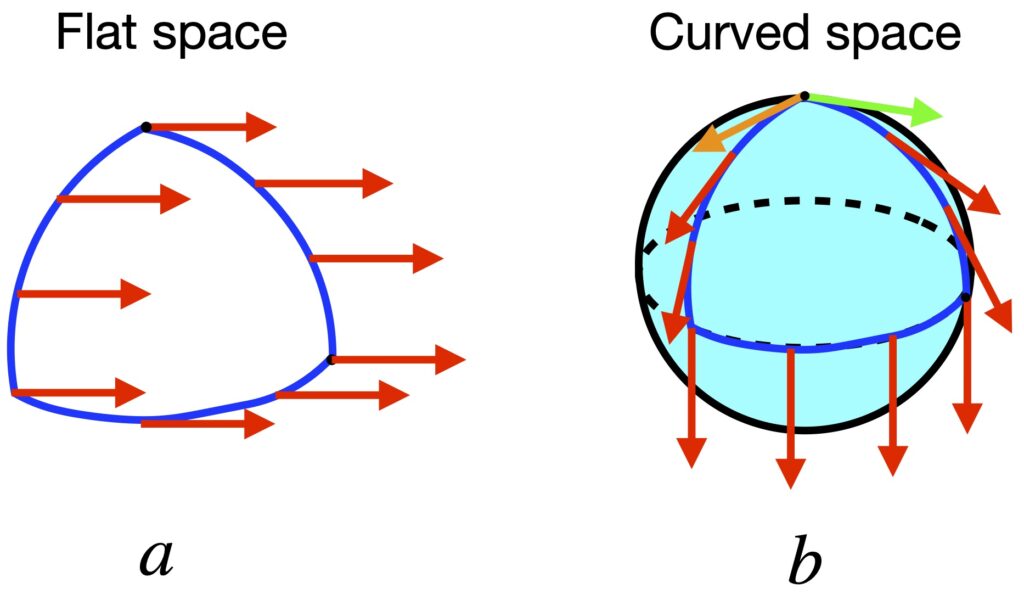

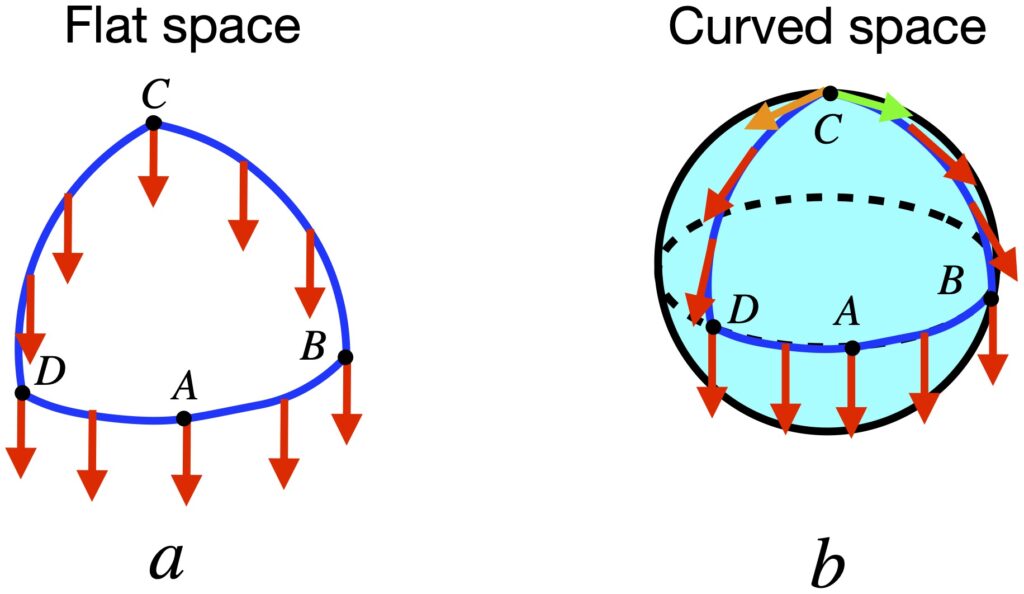

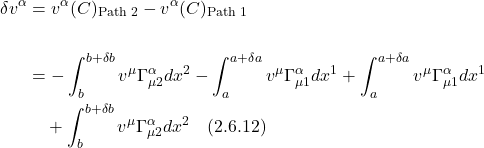

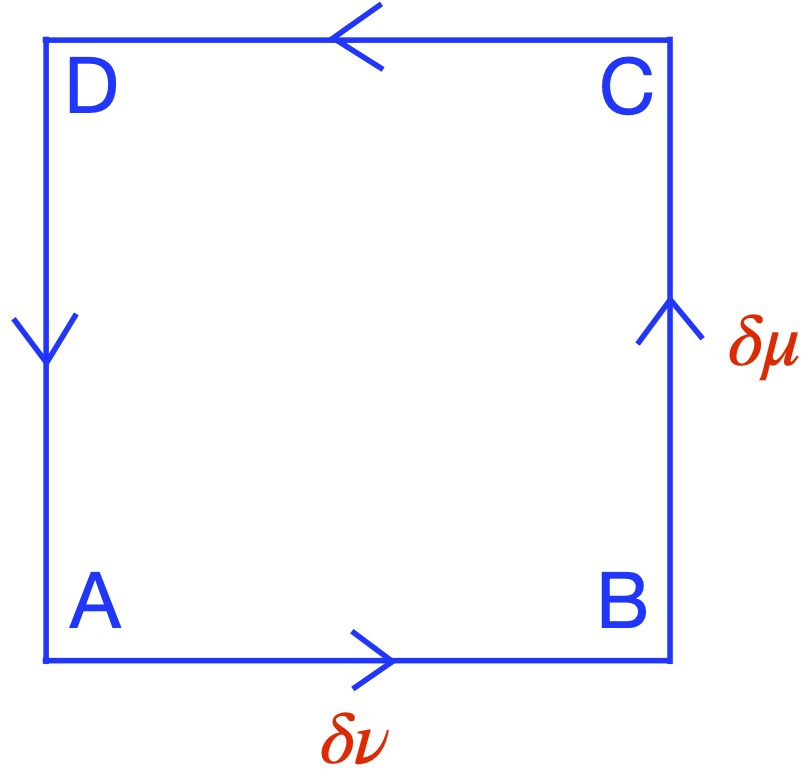

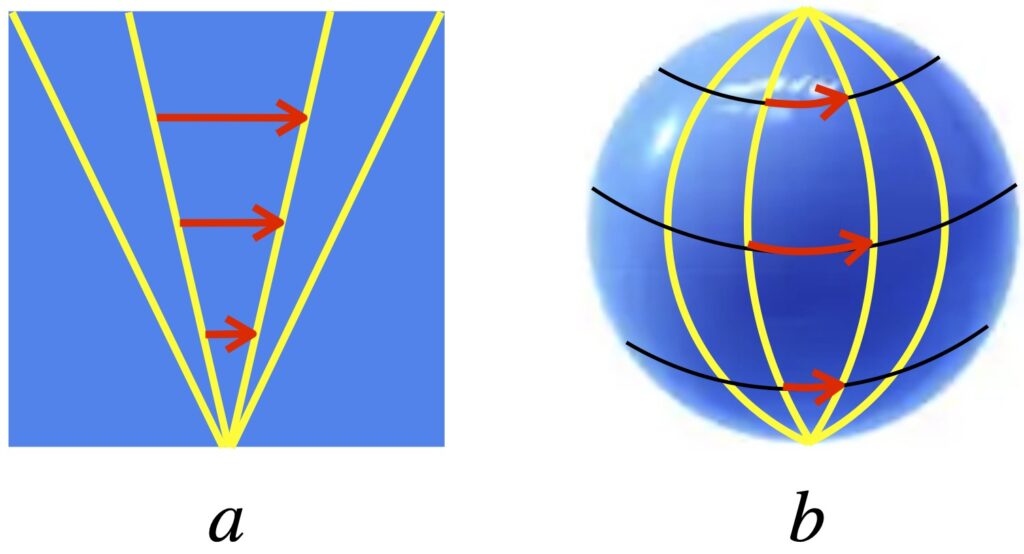

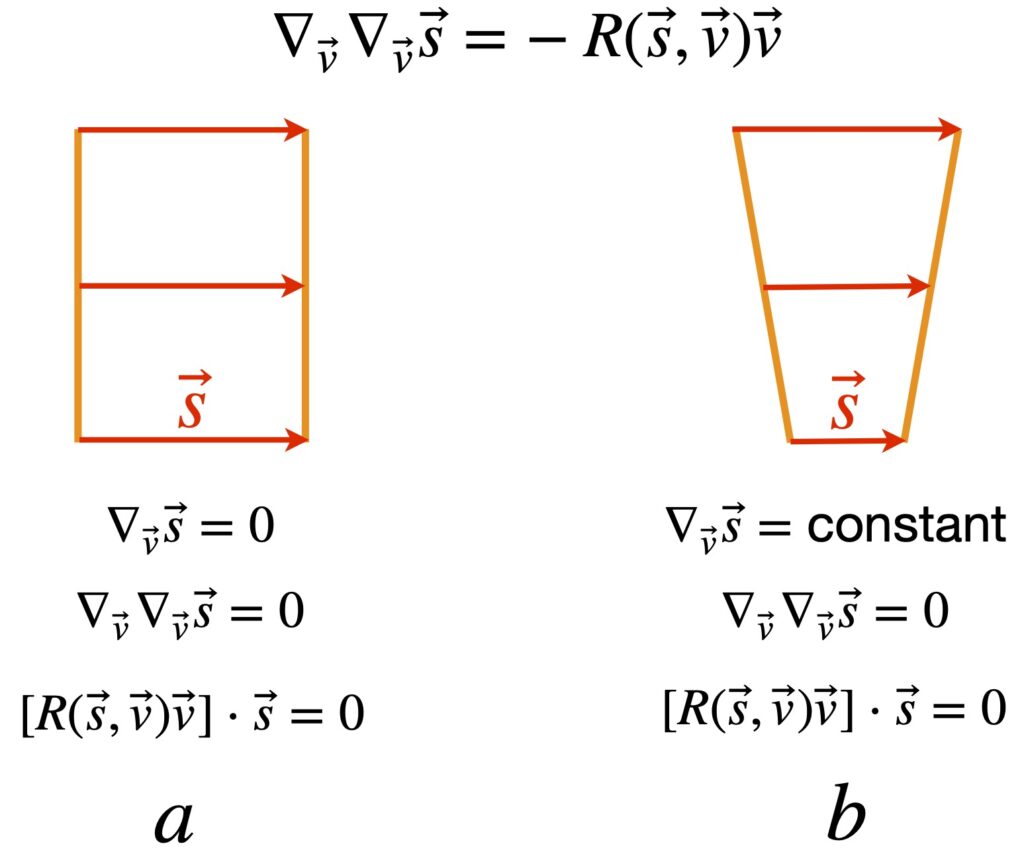

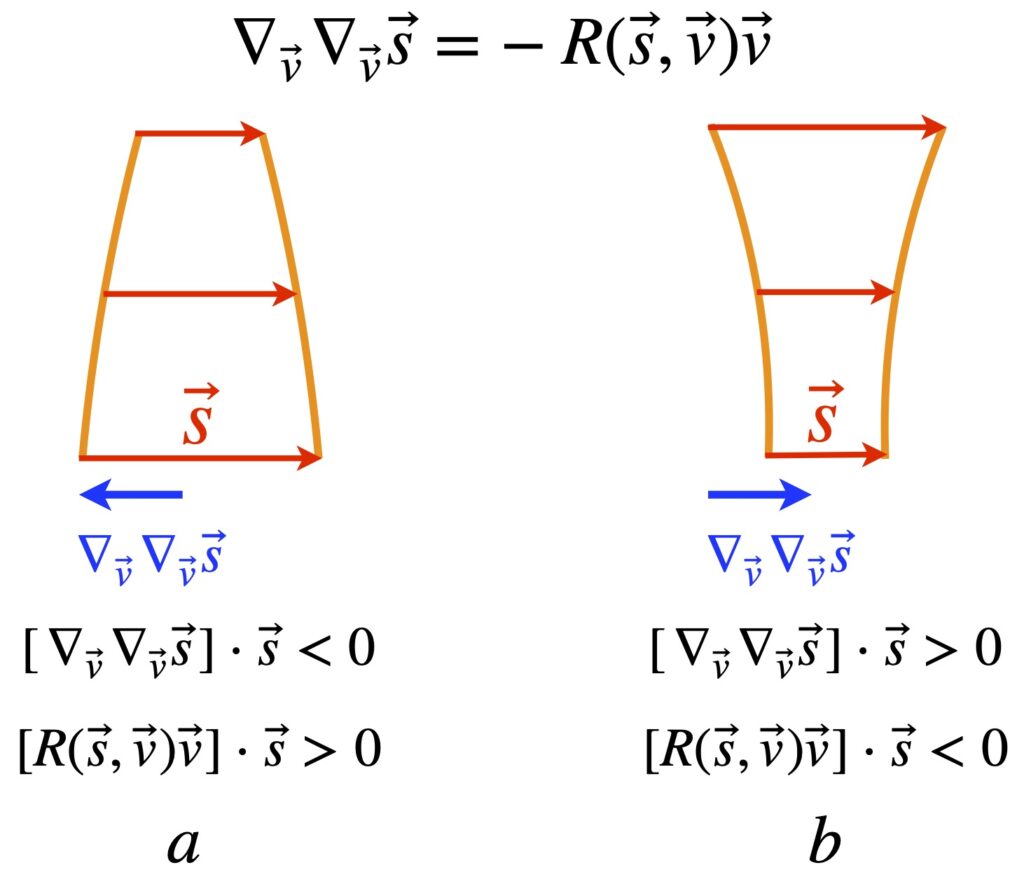

We can see, from figure 2.6.1a, that when we parallel transport a vector from point A to B to C, it will remain unchanged as compared with the same vector parallel transported from A to D to C. However, in curved space like the surface of a sphere (see figure 2.6.2), when we parallel transport a vector from A to B to C, the vector that we end up with at C will differ from the resultant vector after parallel transporting the same vector from A to D to C. To determine whether a space is flat or curved, we’ll apply this same basic idea of parallel transport of a vector in different directions around a closed loop, but will examine this process on a loop of infinitesimal length.

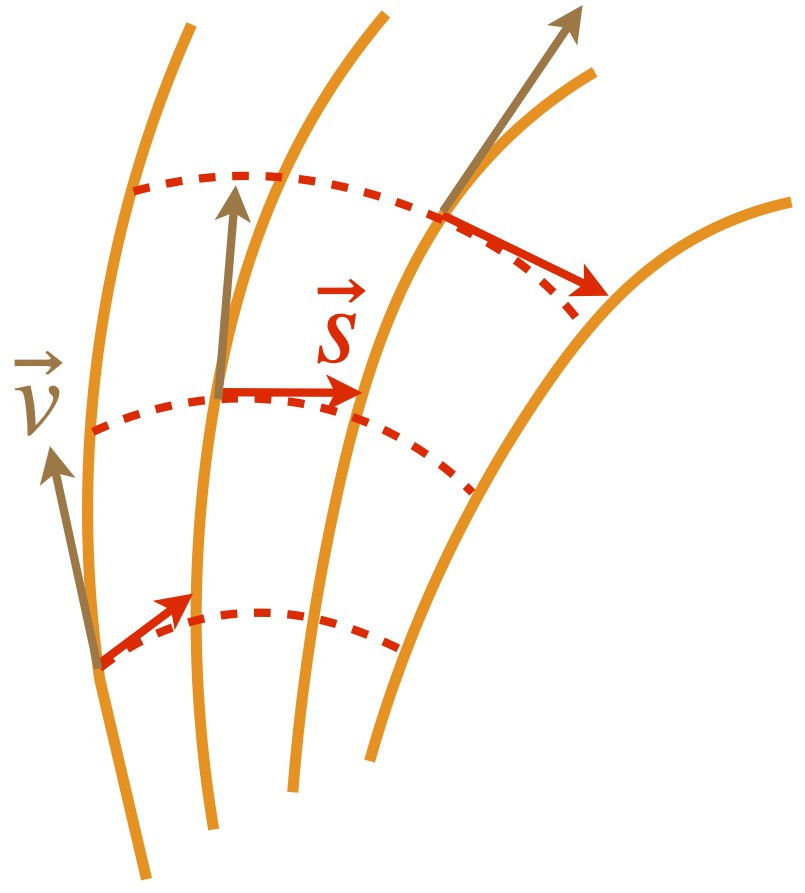

Specifically, as shown in figure 2.6.2, we’ll take a vector, ![]() , and, like in figure 2.6.1 parallel transport it to point C along 2 paths – A to B to C and A to D to C. For each path, we’ll write equations describing these motions with a goal of arriving at a mathematical expression that characterizes the curvature of the space in which we’re working.

, and, like in figure 2.6.1 parallel transport it to point C along 2 paths – A to B to C and A to D to C. For each path, we’ll write equations describing these motions with a goal of arriving at a mathematical expression that characterizes the curvature of the space in which we’re working.

Before we get into the derivation proper, we know that we can consider derivatives as operators that bring about changes in functions. Allowing for minor abuses in notation, we can write:

![]()

Similarly, we can think of the covariant derivative as an operator that brings about a change in a vector as it’s parallel transported along a worldline. For example:

![]()

where we sum up all the little changes brought about by our operator (the covariant derivative), in each little interval, ![]() , take the limit as x goes to zero and add it to the initial vector to get the total change.

, take the limit as x goes to zero and add it to the initial vector to get the total change.

We also know that, since the covariant derivative of a vector that’s parallel transported is zero, we can use equations like the following:

![]()

which implies:

![]()

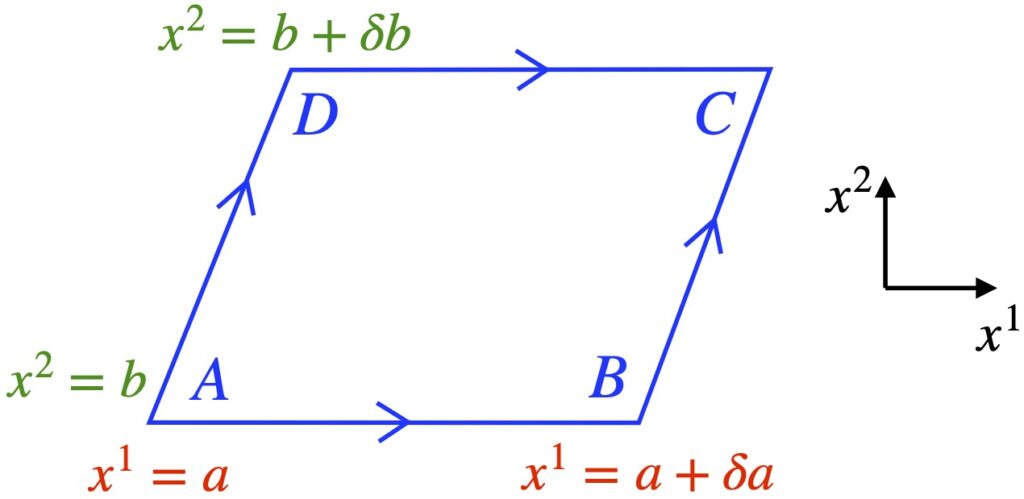

Given these tools, let’s begin with parallel transport of vector ![]() from A to B along the

from A to B along the ![]() . We have:

. We have:

Note that in eq. (2.6.5), and subsequently in this discussion, we’ve moved ![]() to the left side of the equation.

to the left side of the equation.

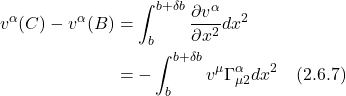

The equations for parallel transport of ![]() from B to C are:

from B to C are:

![]()

and

The net change for Path 1 (i.e., the path from A to B to C) is:

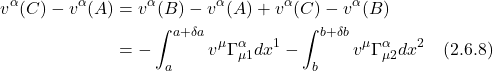

Next, we turn our attention to Path 2, the path from A to D to C. We’ll begin with parallel transport from A to D. We have:

The equations for parallel transport from D to C are:

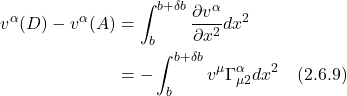

For the entirety of Path 2, the equations are:

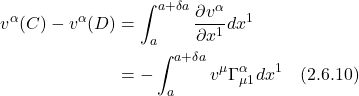

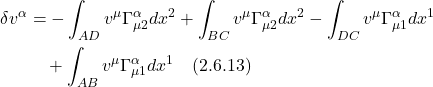

The difference between the vectors transported along Path 1 and Path 2, when they get to C, is given by:

We rearrange terms such that ![]() terms and

terms and ![]() terms are together:

terms are together:

Notice that the integrands in the integrals ![]() (which represents

(which represents ![]() transported from A to D) and

transported from A to D) and ![]() (which represents

(which represents ![]() transported from B to C), are the same. These vectors are parallel but separated by

transported from B to C), are the same. These vectors are parallel but separated by ![]() . What we’d like to do is parallel transport the

. What we’d like to do is parallel transport the ![]() vector to the

vector to the ![]() vector so we can compare them directly. This will give us the

vector so we can compare them directly. This will give us the ![]() component of the

component of the ![]() . To do this, we take the Taylor series expansion of the vector at D in the

. To do this, we take the Taylor series expansion of the vector at D in the ![]() direction. Or, the way I like to think about is: take the vector at D and parallel transport it to the resultant BC vector at C by taking the derivative of the vector at D with respect to

direction. Or, the way I like to think about is: take the vector at D and parallel transport it to the resultant BC vector at C by taking the derivative of the vector at D with respect to ![]() , then multiply it by

, then multiply it by ![]() – the infinitesimal displacement to C – similar to what we did in parallel transporting our other vectors.

– the infinitesimal displacement to C – similar to what we did in parallel transporting our other vectors.

Likewise, the vectors resulting from parallel transport from D to C and A to B are parallel. Thus, we’ll compare them in the manner described above for the A to D and B to C parallel transported vectors to get the ![]() component of

component of ![]() . The results are:

. The results are:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \delta v^{\alpha}& =-\int_{A D}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha}+\delta a \frac{\partial}{\partial x^{1}}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha}\right) \ldots\right) d x^{2}+\int_{B C} v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha} d x^{2} \\ &\quad-\int_{D C} v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha} d x^{1}+\int_{A B}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha}+\delta b \frac{\partial}{\partial x^{2}}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha}\right) \ldots\right) d x^{1} \\ \\ &= \int_{b}^{b +\delta b} \Biggl[-v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha}-\left(\delta a \frac{\partial}{\partial x^{1}}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha}\right) \ldots\right) +v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^{\alpha}\Biggr] d x^{2} \\ &\quad\int_a^{a+\delta a} \Biggl[-v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha} +v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha}+\left(\delta b \frac{\partial}{\partial x^{2}}\left(v^{\mu} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^{\alpha}\right) \ldots\right)\Biggr] d x^{1} \quad \text{(2.6.14)} \end{align*}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-13b2f67aa9909cec1d07c82f745bdd08_l3.png)

After cancelling the ![]() terms of opposite sign in eq. (2.6.14), we’re left with:

terms of opposite sign in eq. (2.6.14), we’re left with:

![]()

This next step is where I become confused. In the video from Robert Davie and other sources that present this derivation (e.g., Scott Hughes, General Relativity, at 1h 05min of Lecture 10, MIT Opencourseware; Bernard Schutz, A First Course in General Relativity, p. 159), it’s said that, because we’re working with infinitesimal distances, the integrals in eq. (2.6.15) become just the area of the loop,![]() . Thus, we can pull out the

. Thus, we can pull out the ![]() ,

, ![]() terms and dispense with the integral to get:

terms and dispense with the integral to get:

![]()

To see how I reconcile this, click .

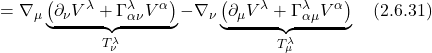

At this point, we expand out the expression in the brackets in eq. (2.6.16) using the product rule, swap some dummy indices and where appropriate, make the following substitution for partial derivatives: ![]() . This leads to:

. This leads to:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \delta v^\alpha & \approx \delta a \delta b\left[-\frac{\partial}{\partial x^1}\left(v^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha\right)+\frac{\partial}{\partial x^2}\left(v^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha\right)\right] \\ & =\delta a \delta b\left[\frac{\partial v^\mu}{\partial x^2} \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha+\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha}{\partial x^2} v^\mu-\frac{\partial v^\mu}{\partial x^1} \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha-\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha}{\partial x^1} v^\mu\right] \\ & =\delta a \delta b\left[-v^v \Gamma_{v 2}^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha+\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha}{\partial x^2} v^\mu--v^v \Gamma_{v 1}^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha-\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha}{\partial x^1} v^\mu\right] \\ & =\delta a \delta b\left[-v^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 2}^v \Gamma_{v 1}^\alpha+\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha}{\partial x^2} v^\mu--v^\mu \Gamma_{\mu 1}^v \Gamma_{v 2}^\alpha-\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha}{\partial x^1} v^\mu\right] \\ & =\delta a \delta b\left[\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha}{\partial x^2} v^\mu-\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha}{\partial x^1} v^\mu+\Gamma_{\mu 1}^v \Gamma_{v 2}^\alpha v^\mu-\Gamma_{\mu 2}^v \Gamma_{v 1}^\alpha v^\mu\right] \\ & =\delta a \delta b\left[\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 1}^\alpha}{\partial x^2}-\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\mu 2}^\alpha}{\partial x^1}+\Gamma_{\mu 1}^v \Gamma_{v 2}^\alpha-\Gamma_{\mu 2}^v \Gamma_{v 1}^\alpha\right] v^{\mu} \quad \text{(2.6.17)} \end{align*}](https://www.samartigliere.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bfdcd170403d924dc1829d97ebaf0d9d_l3.png)

When we take the limit as ![]() and

and ![]() go to zero, we get the difference in the parallel transported vectors at point C:

go to zero, we get the difference in the parallel transported vectors at point C:

![]()

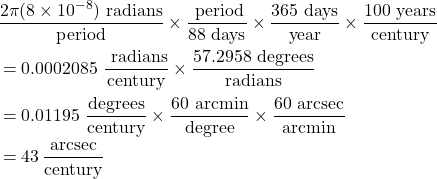

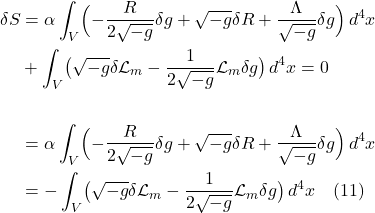

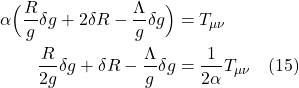

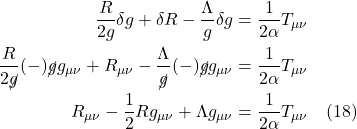

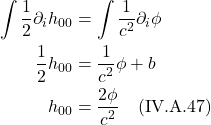

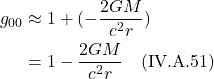

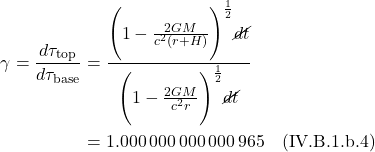

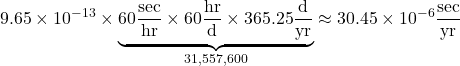

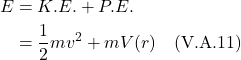

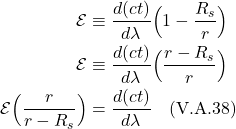

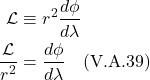

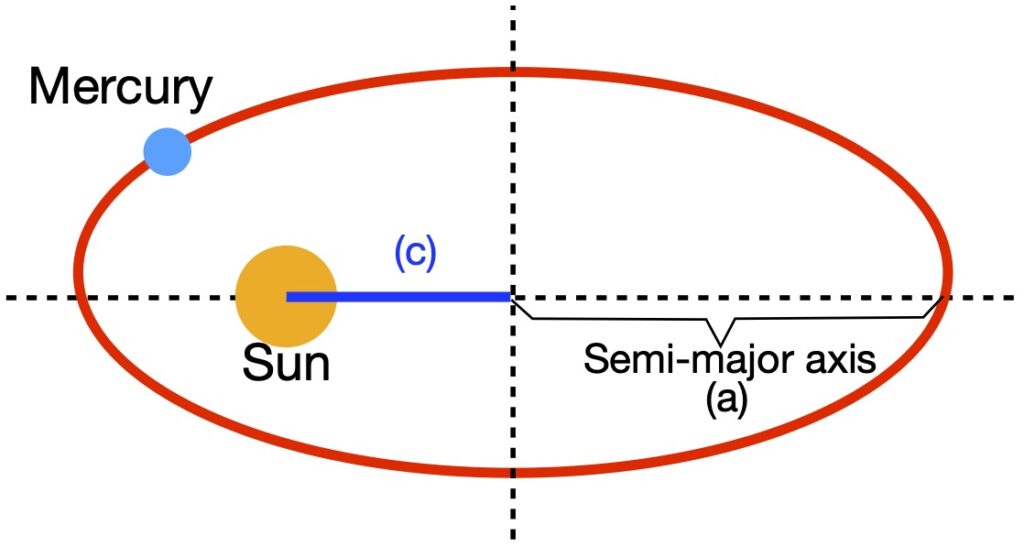

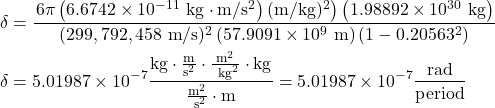

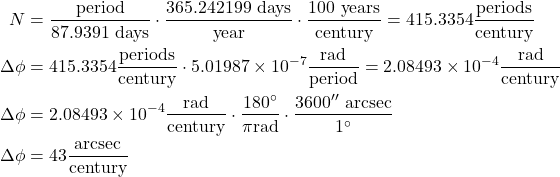

When ![]() = 0, it means the space we’re working with is flat. If it’s nonzero, it means the space is curved. The operator that ultimately makes this differentiation is the expression in brackets in eq. (2.6.18):